Download the latest edition of our guide

We’re excited to announce the 5th Edition of the Wheels for Wellbeing Guide to Inclusive Cycling was officially launched on September 25th, 2025.

There’s been huge progress in national-level consideration of pan-impairment, pan-modal Disabled people’s mobility needs over the past five years.

Our updated 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling aims to support campaigners, policy makers, decision makers and designers to understand the fundamentals of inclusive active travel, so that all Disabled people can have the option to make the walking/wheeling, cycling and multi-modal journeys that we want and need to.

If you are interested in active travel, you might like to view our resources page.

Guide downloads, links and notes

Downloads

Download the 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling as a Word document

Download the 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling as a pdf

Launch event webinar recording (includes BSL interpretation and captions)

British Sign Language (BSL) 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling foreword and key recommendations

Easy Read of the 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling: Summary and key recommendations

Download the Easy Read of the summary and key recommendations as a Word document

Download the Easy Read of the summary and key recommendations as a pdf

Note on using the 5th Edition Guide to Inclusive Cycling:

This online version of the Guide to Inclusive Cycling has been provided for people who find web-based documents more accessible than downloads. For most people, the Word and pdf downloads are likely to have better formatting and be more readable, so we recommend using them if possible. External links should work in Guide formats: please get in touch if any do not work. Internal links between Guide sections will work in downloaded formats, but may not work for everyone in this online version.

References are all at the end of this online version of the Guide. References are at chapter ends in the downloadable versions. In all cases, references are Chicago formatted.

Contents

Contents – page 1

Foreword – page 4

1 The Guide to Inclusive Cycling: Our Approach – page 6

1.1 Our services – page 6

1.2 Our principles – page 7

1.2.1 Equity – page 7

1.2.2 Mobility Justice – page 7

1.2.3 The Social Model of Disability – page 7

1.3 A Rights-Based Approach – page 8

1.3.1 Language and Ethos – page 8

1.3.2 Representation and Imagery – page 10

1.3.3 Inclusive Design and Consultation – page 10

1.4 Chapter 1 Summary Recommendations – page 12

1.5 Chapter 1 References – page 12

2 Disabled people and Cycling – page 13

2.1 Disability in the UK – page 13

2.2 The Equality Act – page 14

2.3 Disabled Cyclists and their Cycles – page 15

2.3.1 Types of cycles and their costs – page 16

2.3.2 Considering costs of cycling for Disabled vs non-disabled people – page 18

2.3.3 Cycling and Mobility – page 19

2.3.4 Which is Easier: Cycling or Walking? – page 19

2.3.5 Benefits of Cycling for Disabled People – page 20

2.3.6 Barriers to Cycling for Disabled people – page 21

2.3.7 Focus on: Neurodivergent people and cycling – page 23

2.4 Chapter 2 Summary Recommendations – page 25

2.5 Chapter 2 References – page 26

3 Accessible cycling facilities – page 28

3.1 Accessible Cycling Infrastructure – page 28

3.1.1 Physical accessibility and safety – page 29

3.1.2 Barriers – page 34

3.1.3 Works and Maintenance – page 35

3.2 Parking and storage – page 36

3.2.1 Stands and spacing – page 37

3.2.2 Access – page 37

3.2.3 Shelters and security – page 38

3.2.4 Charging – page 38

3.3 Supporting infrastructure – page 38

3.3.1 Sales, hire, breakdown and maintenance – page 38

3.3.2 Public realm infrastructure – page 39

3.3.3 Multi-modal journey integration – page 39

3.4 Chapter 3 Summary Recommendations – page 41

3.5 Chapter 3 References – page 41

4 Equitable Active, Sustainable and Multi-modal Travel – page 45

4.1 What are active, sustainable and multi-modal travel – and why are they important for Disabled people? – page 45

4.1.1 Active Travel – page 45

4.1.2 Sustainable Travel – page 45

4.1.3 Multi-modal Journeys – page 46

4.1.4 Barriers to Active, Sustainable and Multi-modal Travel – page 46

4.2 Making active, sustainable and multi-modal travel inclusive – page 48

4.2.1 Inclusive Cycle Centres – page 48

4.2.2 Inclusive Cycle Training – page 49

4.2.3 Funding – page 49

4.2.4 Public Transport – page 50

4.2.5 Inclusive Hire and Share Schemes – page 51

4.2.6 Inclusive Micromobility and Mobility Hubs – page 52

4.3 Cycles as Mobility Aids – page 52

4.3.1 The Need for Legislative Change – page 52

4.3.2 Our asks for mobility aid legislation – page 54

4.4 Chapter 4 Summary Recommendations – page 55

4.5 Chapter 4 References – page 55

5 Getting It Right – page 58

5.1 Policy – page 58

5.2 Training – page 59

5.3 Consultancy – page 60

5.4 Good Practice Case Studies – page 61

5.4.1 Walking/Wheeling and Cycling – page 61

5.4.2 Imagery and Representation: the Wheels for Wellbeing Photobank – page 62

5.5 Chapter 5 Summary Recommendations – page 63

5.6 Chapter 5 References – page 63

6 Summary of Recommendations – page 65

7 Conclusion – Future-proofing Equitable Active Travel – page 67

7.1 Legal change – page 67

7.2 Cultural change – page 68

7.3 Embedding equity – page 69

7.4 A final note – page 69

7.5 Chapter 7 References – page 69

Foreword

It is with great pride that I am introducing our 5th edition of Wheels for Wellbeing’s Guide to Inclusive Cycling!

Eight years on from its first edition, our free Guide continues to be a unique resource for anyone with an interest in seeing cycling become a true choice for all Disabled people. The Guide is regularly quoted, both nationally and internationally, and we take very seriously the need for it to stay relevant and accurate. Since the 4th edition was launched, we have learnt so much more and developed our thinking further – and we’re enthusiastic to share this knowledge as widely as possible. And of course, the context around us has changed, in no small part thanks to our influence and that of other Disabled people’s organisations.

I want to extend my thanks to the Rees Jeffreys Road Fund whose funding allowed us to complete this fifth edition of the Guide. But please note that authorship and responsibility for the contents (including any errors or omissions) rests solely with Wheels for Wellbeing and that the Guide does not necessarily reflect the views of the Rees Jeffreys Road Fund.

Whether you’re interested in transport equity and justice, accessible active travel policy, campaigning for changes to local infrastructure or national legislation, or looking for expert technical guidance, there is something for you in this latest edition of our Guide – including a brand-new chapter on cycling and neurodiversity. Our authoritative Guide also offers links to further, more detailed resources on our own website and to all external publications mentioned in each chapter. Crucially, it has been designed with care to be accessible to all kinds of readers.

We are passionate about walking/wheeling and cycling being accessible to all, whether for whole journeys or parts of journeys, for transport, leisure or for health. Moving more has the power to transform our lives and our wellbeing – right from childhood through to our older years. In the wake of the pandemic this is more important than ever, as we are seeing the health and activity inequality gaps between Disabled and non-Disabled people widening.

Equally, we’re passionate about Disabled people’s voices being heard loud and clear in this field: as Disabled people who walk/wheel and cycle, we have the power to transform the way cycling and other active forms of travel are both understood and provided for.

Finally, in a world that is bracing against the impacts of climate breakdown it’s essential that Disabled people are not left out of the transition to sustainable, active and shared mobility and at Wheels for Wellbeing we demand a just transition for all.

I hope you enjoy this latest edition and that it equips you to better influence the shape of our walking/wheeling and cycling environment. I also invite you to contact us with any feedback and to discuss how, together, we can make active travel accessible to all at an even faster pace!

Isabelle Clement MBE

Director, Wheels for Wellbeing

Wheels for Wellbeing 336 Brixton Rd London SW9 7AA

Registered Charity number 1120905 Company number 06288610

www.wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk info@wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk 020 7346 8482

Find us on BlueSky Facebook Instagram & LinkedIn @wheelsforwellbeing

© Wheels for Wellbeing All rights reserved

1 The Guide to Inclusive Cycling: Our Approach

Founded in 2007, Wheels for Wellbeing (WfW) is a charity run by and for Disabled people. Our vision is a world in which cycling, active travel and multi-modal journeys are just as accessible, convenient and desirable for Disabled people as they are for everyone else.

1.1 Our services

We work towards our vision through three inter-related services:

- Wheels for Life: Every year, we provide access to cycling for more than 1,000 Disabled people aged from two to 102, at our three inclusive cycling hubs in South London. Using our fleet of more than 350 accessible cycles and with the support of experienced staff and volunteers, some of the most excluded from physical activity and outdoor spaces experience the joy of cycling. We run weekly group sessions away from traffic and offer on-street led-rides and cycle hire.

- Wheels for Change: To make sure that Disabled people are not left out of the shift towards active, sustainable and multi-modal transport, our Campaigns and Policy team works across the four nations of the UK to bring about legal and policy change, influencing local, regional and national decision makers.

- Wheels for Learning: We provide consultancy services, accessibility reviews and training, design guidance and learning resources. We share our expertise with, amongst others, transport planners, highways engineers, designers, architects, public servants, and campaigners.

1.2 Our principles

As a Disabled People’s Organisation (DPO) our guiding principles are: equity, mobility justice and the Social Model of Disability.

1.2.1 Equity

Equity is important to ensure that everyone gets what they need rather than everyone being provided with the same thing. The difference between equality and equity in cycling is beautifully illustrated in the image below, produced by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The image shows how equal cycling provision would result in everyone having the same size, standard two-wheeled bicycle – too big for a child, too small for some adults and impossible for a wheelchair-user. An equitable approach to cycling provision means that a wheelchair-user gets a handcycle and the others have a size-appropriate bicycle, giving everybody the opportunity to cycle.

1.2.2 Mobility Justice

Mobility justice means that instead of providing more resources for people who already have the most transport and mobility choices, priority is given to providing opportunities and resources for those who have least. Too often excuses like “cost” or being “too difficult” are given as reasons to exclude Disabled people from transport and active travel. Mobility justice is a reminder that not only should everyone have the same access to mobility and transport, but that pre-existing inequities must be redressed – see also the Public Sector Equality Duty (p.14)

1.2.3 The Social Model of Disability

The Social Model of Disability was devised by Disabled activists in the 1970s to challenge the Medical Model and the Charity Model that dominated Disabled people’s lives.

In the Medical Model, a disability is something that is wrong with an individual. It is often described as an abnormality, disorder or deficit in the person’s body or cognitive or sensory capacities. The focus is on “curing” the Disabled person through medical interventions and sometimes on preventing disability through fetal screening and termination.

The Medical Model also influenced many charities, especially those founded in Victorian times to “help the poor and disabled”. In the Charity Model, Disabled people are seen as helpless, worthy of pity and needing to be cared for. Services are often based on pity and control, with Disabled people having little or no self-determination.

The Social Model highlights that Disabled people are not disadvantaged by their bodies or capacities but, rather, by a society that excludes on the basis of bodily, cognitive or sensory characteristics (often referred to as “impairments”). In the Social Model, using a wheelchair or a white cane are not seen as disabling: the lack of step-free access and inadequate tactile, Braille or audio information are the disabling factors. These are referred to as “barriers” to participation. Barriers can be physical, social, communication-related, institutional, economic, cultural or attitudinal. Once identified, barriers can be removed.

In summary, the Social Model views disability as a social justice and rights issue, not a medical problem to be cured. This is reflected in the language we use to discuss Disabled people, cycling and active travel.

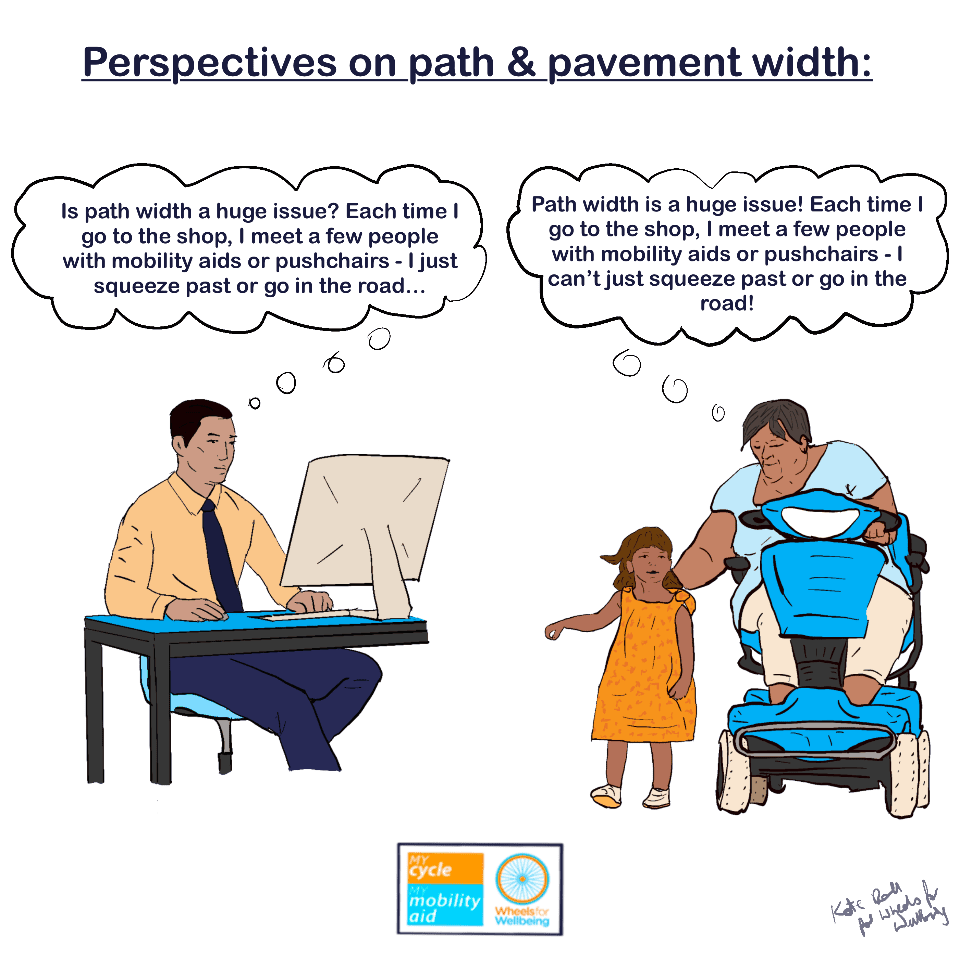

In cycling, the most common barriers that Disabled people report[1] are: inaccessible cycling infrastructure, lack of accessible parking and storage (especially for non-standard cycles), and the cost of non-standard cycles or adaptations to cycles. Cost is a double barrier in the context of the disability income and employment gap[2]. In active travel more broadly, lack of accessible pavements is the biggest barrier to Disabled people’s mobility. This includes the lack of dropped kerbs and tactile markings, uneven and narrow surfaces, pavement parking and street clutter. Pavement inaccessibility can also prevent access to public transport and force Disabled people to rely on more expensive and less sustainable forms of transport, such as taxis and private cars.

1.3 A Rights-Based Approach

1.3.1 Language and Ethos

The language we use reflects our goals and values. To highlight that people are disabled by society rather than by a personal medical problem, many DPOs, including WfW, use the term “Disabled people” rather than “people with disabilities” and use a capital D to highlight the social/political nature of disablement. It’s also important to use words that include Disabled people’s experiences to make active travel and wider society accessible.

For example:

- Bikes vs cycles / adapted vs non-standard cycles:

Expressions such as “bicycle”, “biking” or “on two wheels” are commonly used to discuss cycling. These words exclude users of tricycles, quadricycles and handcycles. They reinforce the misperception that cycling can only be done on two wheels, and that if someone can’t ride a standard two-wheeled bike, then they can’t cycle at all. It is more inclusive to say “cycle/s” rather than “bike/s”. This also helps avoid confusion with motorbikes. When we want to be clear about specific types of cycles, we refer to a “standard cycle” or “standard two-wheeled bike” and “non-standard cycles” for everything else, such as cargo cycles, tandems, trikes, and handcycles. We do not use the terms “adapted” or “adaptive” to refer to non-standard cycles, since calling all non-standard cycles “adapted” gives the impression that everything has to be especially altered before a Disabled person can use it. It also suggests that trikes, tandems and handcycles do not exist in their own right, when in fact the reverse is true. The first cycle to be invented was a handcycle, circa 1655.[3] So, we could refer to standard bikes as adapted handcycles! We only ever call a specific cycle “adapted” when it has been modified in bespoke ways to meet the needs of an individual or specific group of people.

- Walking/wheeling and cycling:

There has been a tendency to use “walking and cycling” to describe active travel. This explicitly ignores wheelchair users and users of wheeled mobility aids other than cycles. We use the more inclusive phrase “walking/wheeling, and cycling”. A bit like the universal wheelchair symbol, “wheeling” draws attention to the presence, access needs and rights of all Disabled pedestrians.

- Words to describe active travel infrastructure:

These can also suggest discrimination or exclusion. For example, historically segregation has been bad for Disabled people and other minoritized groups. It is therefore more inclusive and more accurate to call for “protected” rather than “segregated” cycle tracks.

The words we use about active travel have consequences. Our research[4] shows that local authorities and transport providers are most likely to refer to Disabled people as pedestrians, car drivers and bus or taxi users.

It is rare for authorities to remember that Disabled people can cycle and use faster amplified mobility aids such as class 3 “invalid carriages” (mobility scooters and powerchairs that go up to 8mph). In our research, only 2% of all references to Disabled people were to “cyclists”.

If Disabled people are not recognised as users of faster mobility aids, then cycling infrastructure will not be designed to accommodate us.

1.3.2 Representation and Imagery

Just like language, imagery is important. If Disabled people are not made visible in active travel then we will be forgotten in planning and policy-making, or at best be an afterthought. Lack of representation can also impact Disabled people’s own ambitions: if we have never seen the range of cycles available, or people who look like us cycling, then we are likely to believe that cycling is only for non-disabled people using two-wheeled cycles.

There has been some effort in recent years to move away from representing cycling solely with images of non-disabled, sporty white men riding bicycles in an athletic or competitive context. However, representations of non-standard cycles and visibly Disabled cyclists remain rare. Similarly, it is unusual to see anything other than the standard two-wheeled bicycle used to represent cycling, even when efforts are made to encourage, for example, the use of cargo and family cycles.

To redress this imbalance, and supported by funding from Active Travel England, we launched a photobank of Disabled cyclists that provides publicly available, free to use, fully consented images[5]. These images show a variety of Disabled cyclists riding a range of cycles in different contexts – largely utility cycling, to encourage representations of Disabled people undertaking everyday active travel, rather than elite or specialist para sports. We hope everyone will make good use of these images and help to change perceptions about cyclists and their cycles.

1.3.3 Inclusive Design and Consultation

Active travel infrastructure that is accessible to Disabled people is accessible for the whole population for the whole of their life course, including older people, families, pregnant women, people with temporary injuries or health conditions and even those with luggage. This requires inclusive design, which in turn requires inclusive consultation.

1.3.3.1 Inclusive design:

“Inclusive design goes beyond providing physical access and creates solutions that work better for everyone, ensuring that everyone can equally, confidently and independently use buildings, transport and public spaces. An inclusive environment is one that can be used safely, easily and with dignity by all. It is convenient and welcoming with no disabling barriers and provides independent access without additional undue effort, separation or special treatment for any group of people.”[6]

To achieve inclusive design, it’s essential to begin with current best practice standards and guidance for accessibility and inclusion. These should be viewed as a floor not a ceiling because as knowledge and technology develops, there will always be opportunities for innovations and improvements in accessibility.

Inclusion and accessibility should be starting points for any design: it’s much cheaper and more effective to begin with accessibility than to try and retrofit afterwards. It’s crucial to take an inclusive design approach where there are environmental constraints, so that no-one is ever completely excluded.

1.3.3.2 Inclusive consultation

Inclusive consultation must be carried out for all schemes. It must provide clear information about what is proposed, where, when and why. Information must be provided in a range of accessible formats, online and in person. This includes Word or open document formats as well as pdf and image files, including alt text, large print, easy-read and printed versions, available as default, without people having to search for them or make special requests. For in-person sessions, BSL, lip-reading or a palantypist should be easy to request. People must be able to provide feedback in a range of ways, including in-person, over the phone (including textphone), and directly via email and physical mail. Online surveys only work for people who have access to the internet, can write in English and have enough spare time and energy to do so. We often hear Disabled people described as a “hard to reach group.” But Disabled people are only hard to reach when consultations use inaccessible methods!

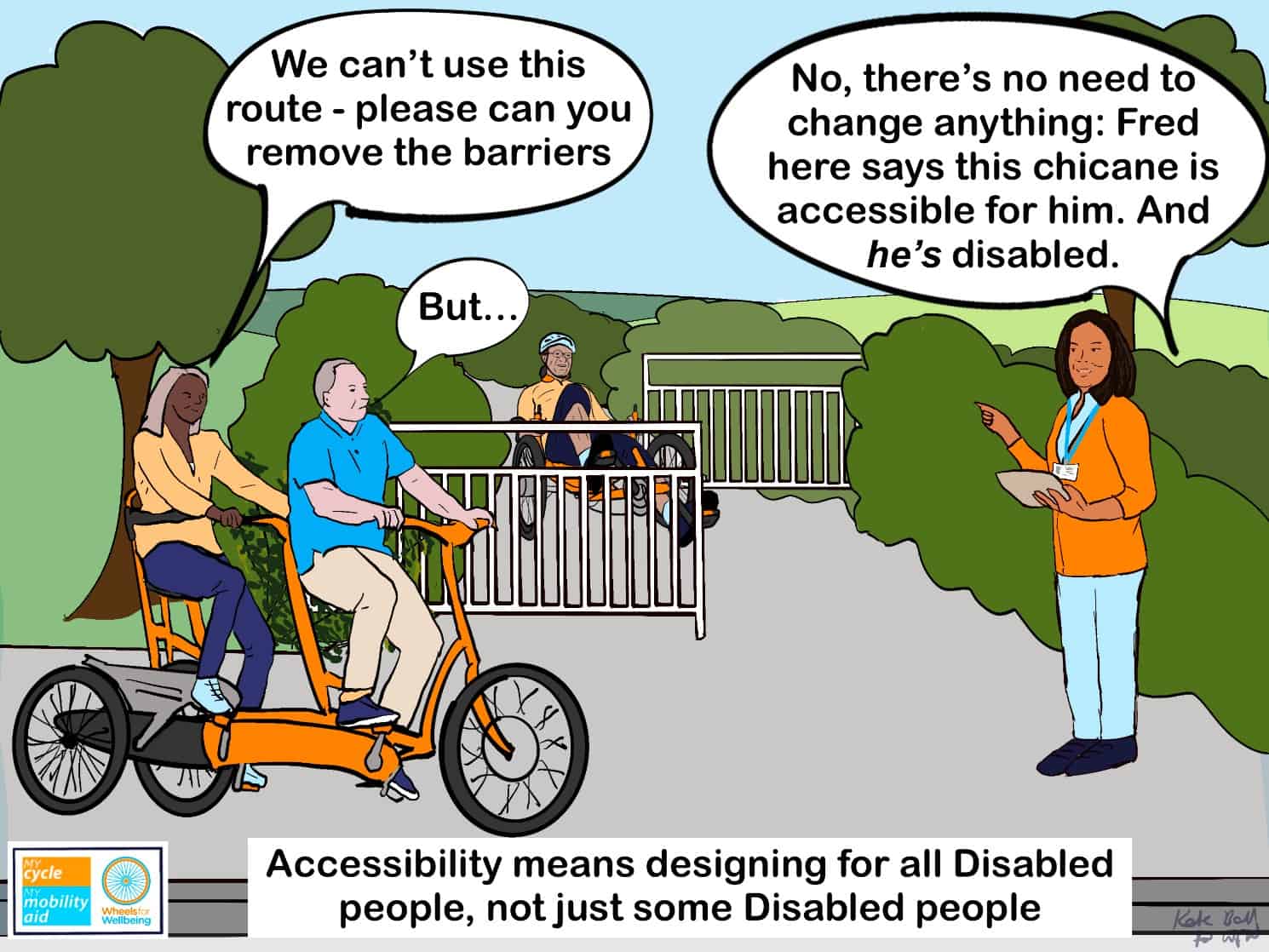

It’s important that consultations are designed to facilitate genuine and meaningful conversation and to incorporate and respond to contributions made by local groups. At the same time, consultations must also include expert input: while local Disabled people are important stakeholders and have key local knowledge, they may not be pan-mode, pan-impairment experts. Designers and decision makers must never use the opinions of a few local people to justify creating schemes that fall below national accessibility standards. Local consultation must be used to improve, not reduce, accessibility.

Genuine consultation and inclusive design are rooted in the principles of co-production, where problems are identified and solutions co-designed by the affected groups. This requires a willingness to listen and let go of pre-conceived ideas, to innovate and to pay Disabled people for our time and expertise. It also requires being open to testing out new ideas and designs, then reviewing and refining them. All of this takes time and resources.

1.4 Chapter 1 Summary Recommendations:

- The principles of equity, mobility justice and the Social Model of Disability form the foundations for accessible active travel.

- Inclusive language and imagery must be used to promote and reflect equal rights for Disabled people and others with protected characteristics and those experiencing socioeconomic deprivation.

- Inclusive consultation and co-production are essential to development of accessible regulations, policies and strategies, infrastructure and implementation of schemes.

2 Disabled people and Cycling

2.1 Disability in the UK

There are 16.1 million Disabled people in the UK – nearly one quarter (24%) of the population[7]. Disabled people come from all backgrounds and no two Disabled people are the same. Many factors beyond impairment shape a Disabled person’s experiences and needs. For example, an older, queer, woman of colour will have very different experiences to a young, heterosexual, white man, even if they are both powerchair users. The term that is often used to explain this is “intersectionality”[8] or “intersectional factors”. Even so, Disabled people share significant disadvantages – particularly economic, health and mobility inequalities.

In the UK, only about half of working-age Disabled adults are in employment, compared to 80% of non-disabled people[9]. Working Disabled people tend to be paid less than non-disabled people, with a pay gap of more than 30% for Disabled women[10]. The additional costs of living for Disabled people total more than £1,000 per month[11] and households with a Disabled member are nearly three times more likely to be in poverty than households that do not include a Disabled person[12].

Disabled people suffer economic and employment inequalities partly because of barriers to transport and mobility. More than 40% of UK train stations are inaccessible[13] and only 60% of Disabled adults have a full driving licence, compared to 78% of non-disabled people[14]. And despite 99% of buses having an accessibility certificate, more than half of Disabled bus users report accessibility problems[15]. For many Disabled people, simply accessing an appropriate mobility aid to make a 1km journey is impossible[16] and many do not feel safe or welcome in their local community[17]. The result is that Disabled people make 38% fewer journeys across all transport types than non-disabled people[18].

Wheels for Wellbeing campaigns for equitable access to walking/wheeling, cycling and multi-modal journeys for Disabled people. Mobility and transport, especially active travel, are essential to health, as well as social, economic and leisure participation. We work to ensure that new, active and sustainable transport systems are designed with accessibility and inclusion prioritised from the outset, to make inequality and exclusion a thing of the past. In the UK (except Northern Ireland) equality and access for Disabled people is governed by the Equality Act (2010).

2.2 The Equality Act

The Equality Act became UK law in 2010, except in Northern Ireland. It replaced previous equality legislation including the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act (DDA). The purpose of the law is to protect Disabled people and other groups with protected characteristics from discrimination.

The Equality Act sets out what organisations must do to avoid discriminating against Disabled people. The first obligation is to provide reasonable adjustments. Reasonable adjustments are things that will make a service, building or environment accessible to different Disabled people. This can be anything from moving a display to making aisles in a shop wide enough for access, making sure information is available in accessible formats, or providing specific accessibility features such as ramps, hearing loops and live captioning. What is deemed “reasonable” depends on how easy it will be for an organisation to make a change, and how much difference the change could make to Disabled people. The duty to make reasonable adjustments is anticipatory. This means that organisations and businesses must be aware of the need for accessibility features and provide them as standard practice before any Disabled people face exclusion. Failure to provide reasonable adjustments is disability discrimination.

Public bodies such as local authorities must also meet the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED). As well as making reasonable adjustments, they must actively promote the equality and inclusion of Disabled people. Public bodies often try to show that they have done this by undertaking an Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA or EIA), which should be publicly available.

The Equality Act also prohibits harassment and victimization of Disabled people.

Reasonable adjustments, the PSED and EqIAs are important in our campaigns for accessible active travel. However, organisations may put forward a range of defenses for not complying with the Equality Act and these are judged in each individual case. It can be difficult to use the Equality Act to challenge discrimination: individuals are expected to take a service provider or a public authority to court for each instance of discrimination, and legal aid is only granted in rare cases. The Equality Advisory and Support Service (EASS)[19] exists to provide initial help.

2.3 Disabled Cyclists and their Cycles

Due to a lack of large-scale research, there is no UK-wide, representative data about Disabled people and cycling. However, consistent themes and issues emerge in the research that WfW and other organisations have conducted. This includes data about the types of cycles that Disabled people use, the types of journeys Disabled cyclists make and how crucial cycles are for Disabled people’s everyday mobility.

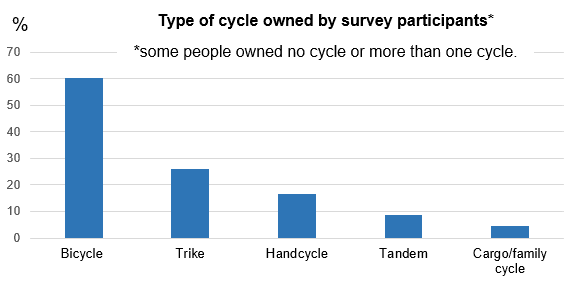

Our research[20] found that the most common type of cycle used by Disabled people is a standard two-wheeled bicycle (60%). Standard, two-wheeled bicycles are the most common type of cycle available to buy. They are the cheapest to purchase, require least space to park and store, and most cycle infrastructure is designed to accommodate them – none of which is the case for other types of cycle. For some Disabled people, the fact that they are no longer visibly Disabled when riding a standard two-wheeled bicycle can feel liberating. However, most still need accessible infrastructure in order to be able to complete their journey.

According to our research, the second most common type of cycle used are trikes/tricycles (26%), including upright and recumbent, tadpole and delta designs (see types of cycles below). Next most common are handcycles, at 17%, which include clip-on wheelchair attachments and one-piece cycles. 9% reported using a tandem, and just under 5% a cargo or family cycle.

2.3.1 Types of cycles and their costs

Non-standard cycles:

-

Have one or more wheels

-

Have a wide range of riding positions, seating, pedalling, braking and other control options

-

May be able to be ridden by one or more person at a time

-

May be able to transport cargo or passengers

A huge range of non-standard cycle models are made by UK and international manufacturers. The second-hand market is strong for certain models – but people who need less common features or cycle types are likely to pay very high prices second-hand, too, if they can find a suitable option at all. For some new cycle types, the delay between ordering and delivery can be many months.

Non-standard cycles can be tried out at some cycle shops, by visiting some manufacturers or inclusive cycle centres.

If there isn’t a non-standard cycle available “off the shelf” to suit an individual’s needs, some manufacturers and cycle shops can add or change features. This can range from aesthetic alterations such as a change of colour to more practical, often essential changes. These might include adding pannier racks and kick stands, relatively basic alterations such as changing the seat or pedal type, as well as more complex and potentially expensive changes such as adding e-assist, changing gears from manual to automatic electric shifters and altering brakes to one-hand or backpedal options.

For very specialist issues, some NHS paediatric OT services make bespoke adaptations for children. The charity REMAP also provides bespoke adaptations for both adults and children through volunteer engineers.

Non-standard cycles are almost always much more expensive than standard cycles, much harder to find in order to learn to ride or try out for suitability, and harder to hire or buy. They are also much harder to get repaired or replaced.

![Graphic showing a range of cycle types and describing the range of features and costs.Costs range from 500 pounds for a standard bike to 13,000 pounds for some e-assist tandem types. Different features available from top left zigzagging to the bottom in orange rectangles. Top words say Cycles Can, then: Have one or more wheels; Be unpowered or e-assist; Be for one or more riders; Have passenger and cargo options; Have different seat types – saddle, seat, with or without harness or restraints; Have different pedal positions and types – hand, foot, handle, clip and strap options; Have different braking and gear options – two hands, one hand, feet, e-assist, automatic; Have storage and manoeuvring features eg folding, lightweight Cycle costs given are: Add e-assist to any unpowered cycle £1k - £3k Clip-on handcycle £3k - £8k (plus compatible wheelchair £3k+) Tandems £1k - £13k Wheelchair transporter duet: £3k - £10k Child carriers: £100 - £1000 Recumbent single cycles: £1.5k - £8k Lightweight folding bikes: £1k - £5k Lightweight bikes: £1k+ Upright / semi-recumbent trikes: £1k - £5k Standard bikes: From £500 Additional features e.g. brake/gear alterations, seat, pedals: ~£100 - £2k+ Sources are getcycling.org.uk, vanraam.com, halfords.com, cyclingweekly.com, direct Google searches “buy + [cycle type]”](https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/11.jpg)

2.3.2 Considering costs of cycling for Disabled vs non-disabled people

Costs of cycles have significant mobility justice implications for service providers and public authorities.

Always consider: Will the cycle enable a Disabled person to get as close as possible to what a non-disabled person with a standard bike can do?

For instance, what could replace a bike for a non-ambulatory, active manual wheelchair user? Handcycling could be a solution – BUT:

A non-disabled person will usually be physically able to make utility journeys of a few miles on a bike costing under £500 – assuming there’s a safe and accessible route.

For our non-ambulatory wheelchair user, basic considerations include:

Arms are much weaker than legs. Manual wheelchair users need to minimise risk of arm or shoulder injuries. These factors mean e-assist is needed for most wheelchair users to make comparable multi-mile utility journeys handcycling.

They will generally need to use their wheelchair at their destination, so the handcycle will usually need to be a clip-on that can be easily removed.

The “cheap” (~£1.5-3k) option of an unpowered, one-piece handcycle is a robust but heavy option. These are likely to be available to try out at inclusive cycling centres and may be suitable for exercising and leisure in controlled environments. These are not usually suitable for on-road, utility journeys and don’t unclip at destinations.

Instead, our cyclist needs a handcycle-compatible wheelchair (~£3k+; it is usually not permitted to attach handcycles to NHS chairs) and an e-assist clip-on handcycle (~£3k+) – a total cost of at least £6k.

Our wheelchair user is likely to have to pay at least 12 times the amount a non-disabled comparator would, just to try out utility cycling.

There are many formal and informal low-cost bike training, hire and donation schemes aimed at non-disabled people, which are often publicly subsidised. There are very few comparable options for Disabled people who need to use non-standard cycles.

2.3.3 Cycling and Mobility

Disabled people use a wide range of cycles, including standard two-wheeled bicycles. E-assist increases the accessibility of cycling for Disabled people (as well as for other groups with protected characteristics, including women and older people), and cycling is often an essential form of mobility for Disabled people.

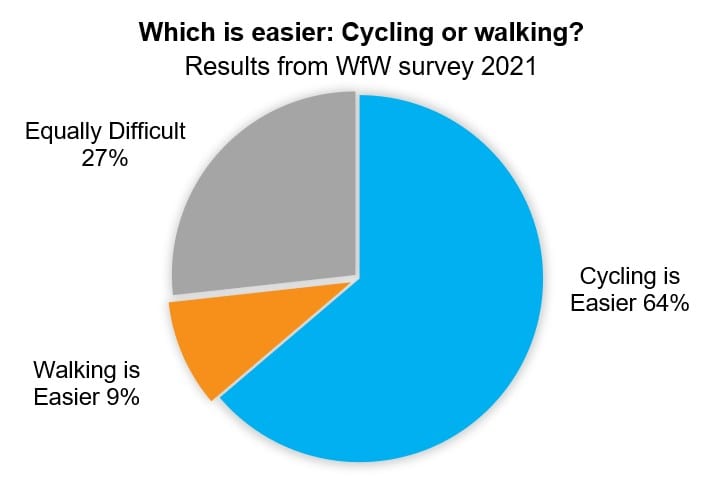

Disabled people who have access to a cycle often cycle on a regular basis. More than one third of our survey participants (36%) cycled every day and more than three quarters (77%) cycled once a week or more. Our survey also highlighted that cycles are essential for Disabled people’s everyday mobility. Nearly two thirds (64%) of respondents found cycling easier than walking, whilst less than one tenth (9%) said that walking is easier than cycling.

2.3.4 Which is Easier: Cycling or Walking?

For many respondents, a standard two-wheeled bicycle provided essential day-to-day mobility that was impossible on foot:

“I have spinal issues and can’t walk any real distance. But I cycle on a normal bike without problem. [It] gives me my independence.”

“I have had MS for 30 years and wish I had realised earlier that I could cycle much better than I could walk!”

At the same time, however, a standard two-wheeled bicycle makes people less visible as Disabled people. Disabled people using standard bicycles are often challenged for using their cycle to replace walking – even though without their cycle they have little or no mobility at all. Blanket “no cycling” policies mean that many Disabled people are excluded from key public facilities such as shopping precincts, public transport hubs and concourses, parks, seaside promenades and green spaces. In chapter 4, we explore the need for cycles to be recognised as mobility aids and discuss our My Cycle, My Mobility Aid campaign.

2.3.5 Benefits of Cycling for Disabled People

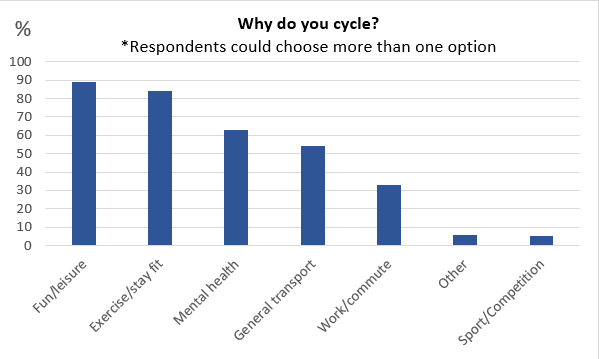

Disabled people cycle for a variety of reasons and experience a range of benefits from it. In our research, the most common reasons reported were as follows: for mental and physical health, including cycling for fun/leisure (89%), to exercise/stay fit (84%), and for mental health (63%). These are especially important given the mental and physical health inequalities that Disabled people experience and the lack of access to the outdoors and green spaces that is essential for wellbeing[21].

“Being a Disabled person who can get out and cycle has been a lifesaver for me. When cycling I feel less disabled; it is the best treatment for my mental health.”[22]

Cycling offers Disabled people independent mobility, with over half of respondents reporting that they cycled for general transport.

“I find it hugely enabling to cycle around for transport and my commute. It keeps me active and mobile, prevents degenerative decline in my muscles and makes me feel good about myself.”

Cycling provides an accessible form of mobility and transport for people whose mental health experience makes public transport and/or driving impossible. This is also true for many neurodivergent people.

“My long-term mental health problems make it extremely difficult for me to drive … and the practically obligatory nature of car usage in our society is very disabling for me. … Almost all campaigning and advocacy around disability and transport seems to focus around driving or being driven in cars/taxis. That’s fine, and those needs are important, but I wish just a little bit would focus on those of us for whom cars and driving ARE disabling.”

Cycling offers an essential and health-promoting mode of transport and mobility for many Disabled people. But there are still numerous barriers that make cycling difficult for Disabled people or prevent them from cycling at all[23].

2.3.6 Barriers to Cycling for Disabled people

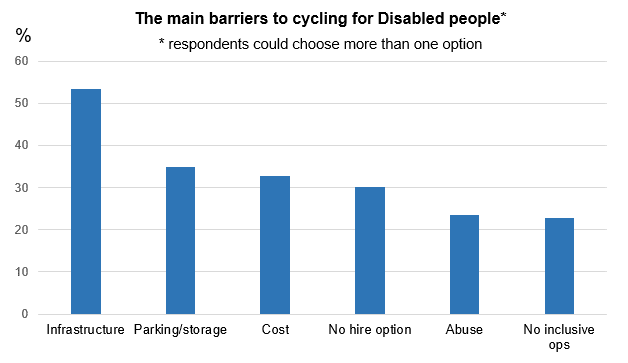

Our 2021 survey found the most common barriers to cycling are as follows:

-

Inaccessible infrastructure (53%);

-

Lack of accessible cycle parking and storage at home and at destinations (35%);

-

The cost of cycles, especially non-standard cycles and/or adaptations to cycles (33%);

-

Lack of opportunities to hire a cycle (30%) – which is particularly important given the issues around cost and parking/storage;

-

Public hostility, harassment and abuse (24%);

-

Lack of inclusive cycling centres or opportunities to try out cycling (23%).

Respondents often reported experiencing multiple barriers to cycling:

“In addition to wishing for wider, more numerous, and more interconnected cycleways, there are 2 major bugbears for me as a disabled cyclist: 1) The quality of supposedly ‘official’ surfaces … 2) Barriers. I ride a recumbent trike, and occasionally an upright tandem, and frequently get blocked by gates or wooden/metal barriers that … are impossible for a wider/longer cycle.”

And some expressed their anger and frustration at these barriers:

“The biggest barrier is cost. Before being disabled I was a keen cyclist. I could buy a high-quality high-performance bicycle for less than £1000, but an entry level handbike will cost three times that amount – over £3000! It is just another area where disabled people are penalised for having a disability that we neither chose nor wanted. WHY ARE ITEMS INTENDED FOR USE BY DISABLED PEOPLE SO MUCH MORE EXPENSIVE? We are being unfairly targeted.”

Overall, there are many barriers to cycling for Disabled people and for a high proportion, these barriers prevent them from cycling at all (e.g., 72% of Transport for All’s respondents[24]). Improved infrastructure guidance in LTN1/20 cycle infrastructure design, the Wales Active Travel Act guidance and Scotland’s Cycling by Design are examples of progress that has been made. A lot still needs to change, however, before Disabled people have equitable access to cycling and active travel.

2.3.7 Focus on: Neurodivergent people and cycling

The needs and experiences of neurodivergent people have been under-recognised and underrepresented in the Disabled people’s movement and in cycling advocacy.

The terms “neurodiversity” and “neurodivergent” originate in the Autistic people’s rights movement but are now often used to describe a wider range of experiences, including ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, as well as mental distress, brain injury and people who are Learning Disabled. Not everyone likes or accepts “neurodiversity/neurodivergent”, and we only use these terms where people have self-defined as such.

2.3.7.1 Benefits of cycling for neurodivergent people

As with other groups of Disabled people, there is no representative data about neurodivergent people and cycling and more research and evidence is needed. But some neurodivergent people have told us about their experiences in our survey and our podcast series. We have also partnered on academic research about autistic children/young people and cycling[25]. Many neurodivergent people who responded to our survey told us that cycling is more accessible for them than public or other modes of transport.

“… because my systems can’t cope with busy public transport well, or at all, such as the tube, if I need to travel into London, on the whole it needs to be via bike.”

“I have ADHD, and I cycle because it is a challenge for me to take public transit … I walk sometimes, but I like to bike because I want to get a bit further faster, and I can easily carry groceries in my bike basket.”

Udit, one of the neurodivergent people who participated in our podcast series, highlighted that as well as transport, cycling provided important wellbeing benefits:

“Cycling is beautiful. I will say that at the outset. It is, to me, it is definitely a means of transport, but one that gives a lot of meaning to my life.”

Udit described the joy of cycling whilst listening to music – which he felt had the added benefit of increasing pedestrian safety:

“The most beautiful thing that happened out of all of that – getting the idea to listen to music on my bicycle. … And as a very unintended consequence, it meant that if there were pedestrians in front of me, they could hear me from a distance. … To me, the sound of music, and the rattle and hum of the road, feel like portable paradises. In listening to music, and especially listening to music from India, it reassures me ‘that is home’. Home isn’t a place, it’s a state of mind.”

Udit also works as a cycling instructor. There is no data that indicates how widely neurodivergent people are employed in the cycling sector, but we know from another podcast participant, Georgia, that it can be a conducive environment for neurodivergent people to work in:

“It is the connection between my love of cycling and the ADHD that really shocked me and really surprised me … I’ve been able to really connect and stick with it for six years, after a career of just chopping and changing, and finding ways to introduce my new interests into my space of work. But apparently, one of the really positive features of ADHD is that many of us really love bicycles. And cycling has absolutely been, not just from a work sense but from a personal sense, a really important part of understanding my own disability, but also managing and finding ways that really helped me manage different symptoms of ADHD, through cycling and through the access that it gives me.”

More research is needed to ensure that neurodivergent people can enjoy all the mobility, health and wellbeing benefits of cycling and to ensure that the cycling sector is an inclusive employer. Alongside the benefits of cycling, we also have some preliminary indications of the specific barriers to cycling for neurodivergent people:

2.3.7.2 Barriers to cycling for neurodivergent people

Recent research[26] exploring the cycling experiences of young autistic people found a number of similar barriers to those experienced by the wider Disabled population. These included the following:

- Cycling was often conceived by parents, schools and instructors solely in terms of riding a standard two-wheeled bicycle. If the child could not ride a bike, it was assumed they could not cycle at all.

- Lack of access to a range of non-standard cycles and the opportunity to try them out.

- Cost, availability and storage for non-standard cycles were often insurmountable barriers; cost was especially significant for growing children.

Learning to cycle is often taught in a way that does not meet the needs of neurodivergent children. Bespoke approaches, delivered at a pace and in a format that matches a student’s learning needs, are much more effective. Nonetheless, even where students have been loaned non-standard cycles and taught in an appropriate manner, wider barriers around cost, storage and access to cycles still often prevent them from cycling.[27]

Finally, neurodivergent people have also reported that hostility and harassment can be a barrier to cycling; and this is all the more significant for those with intersectional and/or racialized identities.

“As much as I am concerned about road rage as any other cycle user, my concerns are amplified because of how I’m racialised and because of the fact that I’m disabled. I have lost count of the number of times that I have been accosted by road rage, coupled with racism and disableism as well.”

In summary:

Neurodivergent people face a range of barriers and benefits to cycling, some of which are shared across the wider Disabled population and others that are specific to them. Further exploration of the barriers to, and benefits of, cycling for neurodivergent people is needed to ensure that cycling, and the cycling industry, is fully accessible to those who wish to participate.

2.4 Chapter 2 Summary Recommendations

- Robust, nationwide, pan-impairment research is needed to deliver high-quality, representative data about Disabled people and active travel.

- Test cases of disability discrimination in active travel need to be supported, preferably by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, to inform national policy and practice.

- An impartial, national accessible cycling service is needed to provide information about cycle types, cycle training and provision of cycles.

3 Accessible cycling facilities

3.1 Accessible Cycling Infrastructure

This chapter gives a brief overview of some of the options for developing inclusive cycling and active travel infrastructure and therefore contains some technical language. Our good practice guides provide more detail on each topic.

Routes for cycling and active travel can be on carriageways, alongside carriageways or on routes without motor vehicles nearby.

On many rural roads and some smaller urban roads, people walking/wheeling, cycling, riding horses and using motor vehicles share the same space.

Many traffic-free cycle routes away from roads are shared with people walking/wheeling (including with dogs), horse riders and with others using the space for non-travel activities. For example, canal towpaths will often include people living in and working from narrowboats, anglers, and people enjoying green and blue outdoor spaces[28].

All cycle routes need to be accessible for Disabled people, including Disabled people using amplified mobility. To achieve this, all cycle routes must be physically accessible, physically safe and socially safe.

3.1.1 Physical accessibility and safety

Cycle routes need to meet, at a minimum, LTN 1/20 Cycle Infrastructure Design guidance[29] standards in England and Northern Ireland, Active Travel Act guidance[30] in Wales, and Cycling by Design guidance[31] in Scotland.

Additional useful documents include Inclusive Mobility (2021) [32], Building Regulations Approved Document M[33] (where part 1 is relevant, we recommend meeting M4(2) at a minimum), BS8300-1:2018 Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment[34] and PAS6463:2022 Design for the Mind – Neurodiversity and the Built Environment.[35]

3.1.1.1 Physical accessibility

Continuously accessible route networks are essential: one inaccessible point can prevent a Disabled person or accompanied group from completing a journey and can put people at risk.

- Complex areas often occur near junctions or transitions between different paths, and in busy places with competing demands for space.

- Design out access friction-points where possible: For example, install raised table crossings to avoid steep dropped kerb gradients.

- Separate infrastructure elements that are likely to create access frictions: For example, install a straight ramp then a level turn rather than a curving ramp.

- Best practice surfacing for cycle tracks is machine-laid asphalt or comparable materials. On some low-use or highly maintained routes, other surfaces may be appropriate.

- Gradients should be less than 1:20, except for ramps[36], with crossfall between 1:100 and 1:50. Level changes reduce accessibility and should be minimised: for example, at-grade, controlled road crossings are usually a more physically accessible option than bridges and underpasses, and are more socially safe.

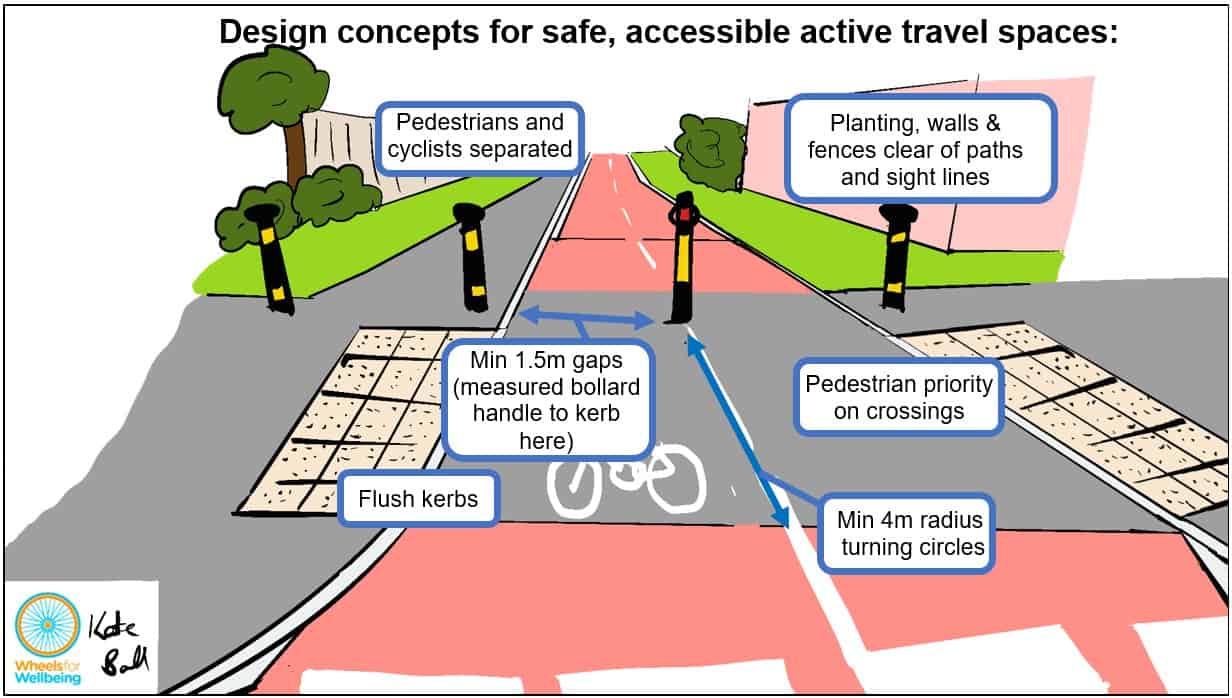

- Widths: Cycle routes should be at least 2m wide for one-way tracks, and at least 3m wide for two-way tracks. The width cannot include kerbs, gutters or drain cover width, and extra width must be provided where edge features reduce the total usable width (LTN 1/20 table 5-3). Where verges are adjacent to cycle tracks, CROW[37] recommends at least 0.5m of firm verge next to cycle tracks, to reduce risk to people who move off the path accidentally.

- Turns: Turns tighter than 4m external radius on routes are not accessible: Turns present a tip hazard to tricyclists, especially when combined with gradients and crossfall. Our swept path analysis guide can help with assessing designs of turns in complex spaces.

- Level changes: Steps of any kind are inaccessible for many Disabled cyclists. Any level change higher than 6mm can be considered a step[38]. Where level changes requiring a ramp are unavoidable, a stepped route with handrails should be included for Disabled pedestrians. Where cycle lifts are required due to space limitations, these should be at least 1.5m wide by 3m long, with roll-in-roll-out layout, preferably paired for access in case of breakdown, and with maintenance and repair contracts with short required repair times. Stations and some workplaces are examples of places that may need cycle-accessible lifts if ramped access cannot be provided.

- Physical hazards on or adjacent to routes must be removed or mitigated.

Road crossings are a key physical access barrier. Crossings often have many hazards and barriers in the same place: Hazards from drivers, uneven surfacing (necessary tactile paving), tight spaces, steep gradients from road camber and dropped kerbs and a step if kerbs are not laid flush. Surfaces wear at junctions – trip hazards frequently develop, especially if less durable colour courses or alternative surfacing materials are used to highlight the space. Designers must ensure crossings will remain accessible long term, even without maintenance.

3.1.1.2 Safety on routes shared with drivers

Where people cycling are expected to share space with drivers, speed limits need to be no more than 20mph, with good enforcement, good sight lines and below 2500 vehicles per day (LTN 1/20 fig 4.1).

Measures including modal filters, speed limit reductions, and physical speed-reducing measures and enforcement can make many urban and rural roads suitable for largely inclusive on-carriageway cycling. Some Disabled people will always need fully traffic-free spaces to cycle but many non-standard cycle users are forced to share routes with drivers because alternative, traffic-free routes are not accessible.

3.1.1.3 Safety on routes parallel to carriageways

Cycle lanes are part of a carriageway and, if not protected by physical measures, will often be driven or parked in. Cycle tracks are separate from a carriageway.

We consider unprotected cycle lanes to be space shared with drivers, whether they are mandatory or advisory.

Protected cycle lanes can only be inclusive on roads with speed limits no greater than 30mph, with crossfall below 2.5%, and with usable widths of 2m (min 1.5m at short constraints).

Buffer zones or physical barriers can protect cycle track users from drivers and from other physical hazards – see LTN 1/20 table 6-1.

3.1.1.4 Safety at cycle route road crossings

Junctions are especially dangerous for cyclists[39]: where protected cycle routes cross roads, accessible protected crossings are needed.

Accessible cycle crossing options can include cyclops junctions[40], cycle stages at light-controlled junctions, parallel crossings[41] and signalised crossings for cycles[42]. A Toucan crossing[43] is a shared space in a complex location; this means they are the least accessible protected crossing option, as they create conflict between people cycling and those walking/wheeling, excluding some Disabled pedestrians and cyclists.

Junction designs that require cyclists to move quickly put slower-moving cyclists at risk from drivers: advanced stop lines[44], cycle early release[45] and two-stage turns are not accessible for many Disabled cyclists and others with protected characteristics.

3.1.1.5 Safety in shared active travel spaces

Spaces shared between people cycling and people walking/wheeling are inaccessible to many Disabled people due to the risk posed by faster cyclists (and amplified mobility users). Horse riders on routes add further risk, but many cycle routes are bridleways or historic routes on which horse riders are permitted. We ask decision makers to consider design, risks and benefits very carefully before designating new active travel routes as bridleways.

Improving the physical accessibility of routes and providing clear user expectations can mitigate some but not all of the inaccessibility issues of shared spaces: we advise that providing a detectable kerb (min 60mm high) separating cycling and walking/wheeling spaces is best practice for accessibility, with good visual contrast between different surface elements.

It is sometimes not possible to provide separate space for users of all modes, especially in very low-use locations. Designers and decision makers need to think very carefully about whether a shared route is necessary or if a more inclusive option is possible. Too often, shared spaces are made as an aesthetic choice, rather than being the best option for accessibility that can be achieved.

3.1.1.6 Safety from physical hazards other than drivers

Traffic-free cycle routes frequently have physical hazards on or next to the route, and on-carriageway routes have some on-route and route-adjacent hazards too. The numbers of deaths and injuries these hazards cause to people walking/wheeling and cycling is not well understood, but it is likely to be considerable[46].

On-route hazards include designed obstacles such as bollards and physical barriers, and maintenance-based hazards such as potholes, leaves and litter.

Route-adjacent hazards can include kerbs, vegetation, drops and water. Route-side water can be a hazard for people walking/wheeling and cycling: similar numbers of people die after falling into water each year as the numbers of pedestrians killed after being hit by a driver.

Walking/wheeling and cycling routes must be safe for everyone to use, with non-driver hazards being regarded as seriously as risk from drivers. Research is needed to work out which infrastructure creates hazards and the safety measures that could make routes inclusive. Examples of safety measures could include edge protection, buffer zones, greater unobstructed surface widths and alternative routes.

LTN 1/20 table 6-1 (separation of cycle tracks from carriageway risk), table 5-3 (additional width at fixed objects) and London Pedestrian Comfort Guidance appendix C (kerb buffers)[47] together provide the beginnings of a framework for considering physical risk and other impacts of on-route and route-adjacent hazards.

In the Netherlands, 60% of seriously injured cyclists admitted to hospital are victims of a single-vehicle accident.[48] Infrastructure causes half these injuries. UK data[49] only includes cyclist deaths and injuries that happen on roads – but traffic-free paths have many on-route and route-side physical hazards too.

3.1.1.7 Social safety

Social safety is how safe people are and how safe they feel from other people in different situations.

People with protected characteristics are less safe and feel less safe[50] in public spaces than people without protected characteristics. London Cycling Campaign’s What Stops Women Cycling in London[51] found that a third of respondents stopped cycling after dark or in winter due to lack of safe routes. The London Cycling Campaign After Dark report[52] provides detail on social safety and lack of safety on cycle routes, including personal accounts of incidents.

Good social safety is essential for accessibility and must be designed into all schemes.

Many people, for instance, enjoy using traffic-free routes through green spaces when travelling during the day and/or as part of a group but cannot use the same routes when alone or at night. In some cases, the social safety of a route can be improved – for example, if buildings fronting onto a traffic-free route are developed, vegetation cut back or barriers removed. Usually, however, alternative road-adjacent routes will need to be provided to create joined-up, accessible active travel networks.

Routes that have open sight lines, are wide enough to turn around on and avoid hazards, that are well overlooked, well used, well lit and well connected, are likely to be relatively socially safe. Routes that are secluded, narrow, with poor sight lines, physical barriers and hazards, poor connectivity and few people using them, are likely to be unsafe.

3.1.1.8 Wayfinding

Wayfinding is too often an afterthought in active travel route design – but a route can only be accessible if it is easy for everyone to follow it.

It must be clear to people cycling where a route goes, and where within a space they should be riding. Measures that help with wayfinding include:

- Tactile demarcation (kerbs and tactile paving) and, where possible, colour demarcation of the cycle route with good contrast[53] between surfaces.

- Continuity of the cycle route: minimising the number of junctions where a designated cycle route gives way (including altering road priority for on-carriageway cycle routes).

- Signage where needed: signs on road routes must comply with TSRGD. Otherwise, signs should:

- Be large enough for route users to see.

- Be made of durable materials.

- Have high contrast between clear lettering/graphics and the background.

- Be positioned so they are easy to see, including from a recumbent position.

- Include distances to destinations with units, not times – Disabled people (and others such as parents with small children) are less likely to move at “expected” speeds. Signs that give times to destinations are not helpful for many Disabled cyclists.

Paths for All have signage guidance for off-road routes[54] and PAS6463 Design for the Mind[55] contains a range of helpful considerations.

3.1.2 Barriers

3.1.2.1 Designed access barriers

Physical access barriers have often been installed to try and prevent antisocial behaviour or dangerous use of traffic-free paths, particularly by people riding motorbikes and some inconsiderate cyclists.

Unfortunately, these designed barriers rarely prevent antisocial behaviour – and in many instances they may increase it by reducing legitimate use of routes. But barriers do prevent access to many Disabled people and others using non-standard cycles or mobility aids.

Physical access barriers on walking/wheeling and cycling routes are likely to be discriminatory under the Equality Act (2010).

Individual Disabled people’s opinions or a trial with a non-standard cycle should never be used to justify installing discriminatory barriers. Instead, the Cycle Design Vehicle[56] dimensions and turning circle should be used, as it has been defined to ensure that all non-standard cycles can use all infrastructure.

Where there is a clear need to prevent car drivers from using cycle routes, vehicle access restriction bollards can be used, spaced with minimum 1.5m gaps between them and with straight-line access for the Cycle Design Vehicle, which has a 4m external radius turning circle.

3.1.2.2 Unintended access barriers

Even when intentional access barriers are removed from routes, they all too often remain inaccessible. This might be because removal of barriers has either caused or not addressed other access barriers in an area. For example, a metal motorcycle barrier may have been removed, but designers may not have noticed that there is no dropped kerb access. Speed bumps may be put in to slow drivers, but can be too steep for mobility aid users to get over when pavements are blocked or don’t exist.

Unintended access barriers break networks in ways that can be hard to get addressed because designers, decision makers and site teams often don’t understand the issues. Good ongoing training and professional development are essential to prevent installation and retention of unintended access barriers.

3.1.3 Works and Maintenance

Works on routes can be routine, planned non-routine, or emergency.

For all works, maintaining walking/wheeling and cycling access on the route is the best option if possible. Any signage and information regarding works must make it clear whether a route is being closed to motor vehicles only or to pedestrians and cyclists as well. If a scheme is affecting public transport, accessible information must be provided regarding any changes, cancellations or diversions, including bus stop moves.

Presently, minimum statutory access standards are provided in Safety at Street Works and Road Works (2013)[57]. We are calling for improvements to these standards to align walking/wheeling access requirements with Inclusive Mobility (2021) and cycling access requirements with LTN 1/20.

Wheels for Wellbeing advise that for accessible provision at works:

Where keeping a route open is impossible, the shortest possible alternative accessible route for walking/wheeling and for cycling must be provided and clearly signposted, and the usual route re-opened as rapidly as possible.

For planned or longer emergency works, landowners or statutory undertakers should provide Disabled people living in and using the area with accessible training in using modified or new routes, including alternative active travel and public transport routes.

Disabled people using cycles as mobility aids must be allowed to pass through works using pedestrian routes without dismounting.

3.2 Parking and storage

Accessible cycle parking and storage is essential for inclusive cycling. E-powered mobility aids such as mobility scooters and innovative aids may have similar parking and storage requirements to trikes and other cycle types. Most fully powered mobility aids are smaller and more able to reverse than cycles. Most fully powered mobility aids are much heavier than most cycles. Batteries often can’t be removed from fully powered mobility aids. Batteries can’t be removed from some e-cycles.

Our Guide to Inclusive Cycle Parking provides more detail on a wide range of cycle parking and storage considerations. A few important elements are outlined below:

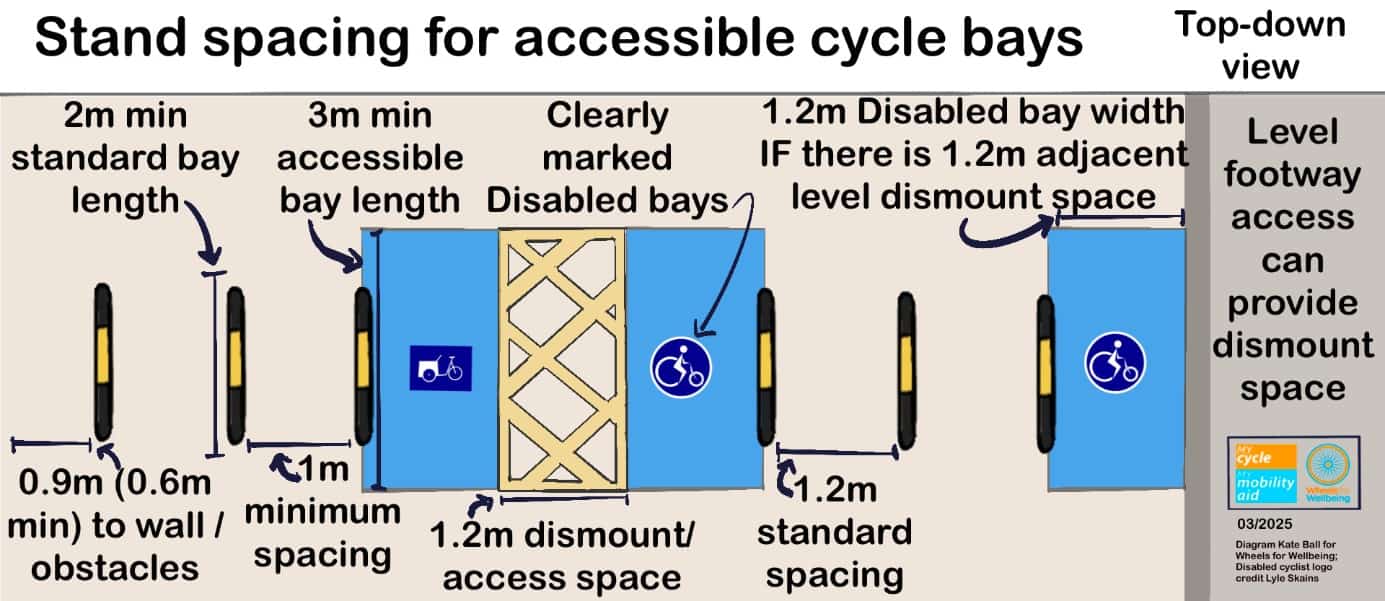

3.2.1 Stands and spacing

Destinations need sufficient accessible stands and bays such that there is always (or almost always) free space – regular monitoring should be carried out capacity added if accessible bays are becoming full.

We suggest that as a minimum, 10% of spaces or at least one space, whichever is greater, should be an accessible bay designated for Disabled cyclists. If a single Disabled space is ever used, another should be added.

All cycle parking needs to be accessible enough that most cyclists, including most Disabled people riding bicycles, will be able to use the “standard” spaces provided rather than needing to use the limited number of large, accessible spaces provided. Stands must be of high quality and installed well, to reduce risk of theft and meet insurer requirements for expensive non-standard cycles (usually Secured by Design Gold)[58].

Disabled people, including those living in, working in and visiting residential homes and sheltered housing, are entitled to choose to cycle and use e-mobility. Accessible cycle and mobility aid parking must be provided at residential and sheltered housing to at least the same levels of provision as all other residential developments, and preferably higher levels, since Disabled and older people are less likely to be able to drive or to walk to public transport stops. Failure to provide for wheeling and cycling is likely to exclude many Disabled people from making independent or supported journeys altogether.

3.2.2 Access

Access must be step-free and not require dismounting, including for the operating of doors. Best practice access allows roll-in-roll-out movement of larger cycle types: very few cycle types can reverse. Turning circles and gradients near to parking are critical.

Marking out cycle bays on design drawings and on the ground is good practice, especially where cycle parking is installed in pedestrian spaces: cycle parking must be installed so pedestrian desire lines are not obstructed by parked cycles.

3.2.3 Shelters and security

Social safety is critical for cycle parking locations. Parking needs to be usable at all times of day and night, and to have low risk of theft.

3.2.4 Charging

E-assist is essential for many Disabled cyclists. At the very least, Disabled cyclists need to be able to charge cycles safely at home, and preferably in longer-term parking as well. Li-ion batteries cannot be charged in very cold conditions. Accessible heated charging locations are therefore needed – either in homes or in designated storage locations.

There are growing concerns about lithium-ion battery fires related to e-cycles. We believe that better regulation of sale platforms is needed, and delivery platforms need to be made responsible for the vehicles and cycles their riders use. These changes could reduce risk of battery fires without unreasonably restricting use of safe, environmentally friendly, efficient e-assist and e-powered mobility aids that Disabled people rely on.

Disabled people must not be prevented or discouraged from using and charging our safe e-assist mobility aids by failure to restrict sale and use of dangerous devices.

3.3 Supporting infrastructure

Accessible cycling doesn’t just require accessible cycle routes and parking, wider infrastructure must also be accessible too.

3.3.1 Sales, hire, breakdown and maintenance

Disabled people’s cycles – and other mobility aids – are often an essential, personal and expensive piece of equipment that we need to use but can’t lift, transport in a car or fix by ourselves. There are limited places to buy, hire or maintain them.

Improving access to cycling for Disabled people will require easy access to local cycle shops and hire centres that stock a wide range of cycle types and are able to provide expert guidance and personalised adaptations. Such services are currently rare and available only through specialist charities or community-interest companies.

We need a full range of routine and emergency maintenance services comparable to that car garages provide, as well as courtesy cycles or accessible alternatives.

Since many Disabled people can’t push or carry a broken cycle home, or even put it into a private car, we need cycle breakdown recovery services comparable to the increasingly available mobility scooter recovery services.[59]

3.3.2 Public realm infrastructure

We’ve considered infrastructure for cycle routes, but wider public realm infrastructure is essential for accessible cycling too: Disabled people need to be able to get between, and sometimes all the way into, destinations while cycling, as well as needing to be able to make longer multi-modal journeys.

Design and ongoing maintenance needs to provide the best possible access for all public areas, particularly for walking/wheeling routes.

Different public areas have different appropriate provisions: for example, it is unlikely to be reasonable to expect the same facilities on a little-used footpath as a busy city-centre space.

Continuous legible and accessible walking/wheeling routes in public spaces are essential. Except for very low-use routes, these should meet BS8300:2018-1 and PAS6463 standards. Seating, shelter including warm spaces and food/drink options, accessible toilets[60] including Changing Places toilets,[61] and sensory design for lighting, sound, heat and crowding[62] are some important additional factors that need to be considered in different public spaces.

3.3.3 Multi-modal journey integration

3.3.3.1 Public transport

Disabled people disproportionately do not drive and do not have access to private vehicles. This means we are disproportionately dependent on public transport, especially to make longer journeys.

Unfortunately, public transport is frequently inaccessible[63] and often unsuitable for making timely journeys to specific destinations, even when it is accessible.

We need improvements in public transport accessibility[64] so that more Disabled people can make the journeys we want and need to make, affordably and sustainably. To make multi-modal journeys, we need to be able to bring our mobility aids onto public transport vehicles. We also need public transport that can accommodate multiple Disabled people at any one time, in addition to baby buggies and luggage.

3.3.3.2 Hire and share schemes

Shared vehicle and rental schemes are mostly inaccessible to many Disabled people, in particular to those who need non-standard vehicles and those who need to transport mobility aids.

Cycle and micromobility hire and share schemes are frequently inaccessible to Disabled people: users routinely need to walk significant distances to shared bays, where cycles may or may not be available. Hire vehicles carry one person only – so Disabled people who need assistance and those who are carers cannot use them. We are working with a range of organisations to improve the accessibility of hire and share schemes and to provide alternatives that work for a greater proportion of Disabled people.

Our Wheels4Me London scheme and a few other pilot schemes provide short-term loans of non-standard cycles (see chapter 4). But more comprehensive, nationwide and longer-term options are needed to enable Disabled people to try out cycling and to progress to owning their own cycle if they wish. For those unable to afford a cycle or without suitable cycle storage, hire and share schemes are likely to remain a primary option for cycling.

3.3.3.3 Taxis and private hire vehicles (PHVs)

Taxis and private hire vehicles provide essential mobility for Disabled people who don’t have access to public transport or private vehicles for some or all journeys. As with public transport, we need more taxis that are able to transport a range of mobility aids, including cycles. Taxi and PHV drop-off/pick-up options and taxi ranks are an important part of Disabled people’s mobility and need to be included in designs.

3.3.3.4 Private motor vehicles

While many Disabled people rely on public transport,[65] many others are unable to use public transport due to inaccessibility[66] and lack of public transport routes.

Reducing the UK’s private vehicle use is extremely important for Disabled people’s health and safety – Disabled people are more likely to be injured or killed in crashes, more likely to be prevented from making journeys by dangerous driving behaviours (including pavement parking), and more likely to be made ill by air and noise pollution.

However, Disabled people’s car use needs to be facilitated: many Disabled people need to use private vehicles to make any kind of journey, including to access cycling opportunities such as reaching off-road venues and to transport larger cycle types. The Motability Scheme[67] is available to Disabled people in receipt of higher mobility rate of certain benefits including Personal Independent Payment[68] and facilitates access to private cars, mobility scooters and powered wheelchairs. Currently, though, it doesn’t enable access to non-standard cycles, and there is no nationwide scheme to make active mobility devices affordable for Disabled people.

Disabled people need affordable accessible vehicles and enough designated parking bays to meet and just exceed peak demand in order to access the mobility and exercise options that work for us.

3.4 Chapter 3 Summary Recommendations

- High-level and detailed designs and ongoing maintenance provision must all be right for infrastructure to have good accessibility.

- High-quality risk assessments and equality impact assessments are essential tools for identifying and designing out or mitigating accessibility problems.

- National and international guidance, research and local knowledge are all important: Where recommendations from different sources differ, use the recommendation that provides best pan-impairment accessibility.

- Different Disabled people have different access needs – and needs sometimes conflict. The job of designers and decision makers is to ensure everyone’s needs are met as well as possible, and that nobody is excluded from making journeys.

- Wheels for Wellbeing resources integrate good practice guidance and evidence to support development of high-quality accessible active travel and public realm schemes.

4 Equitable Active, Sustainable and Multi-modal Travel

4.1 What are active, sustainable and multi-modal travel – and why are they important for Disabled people?

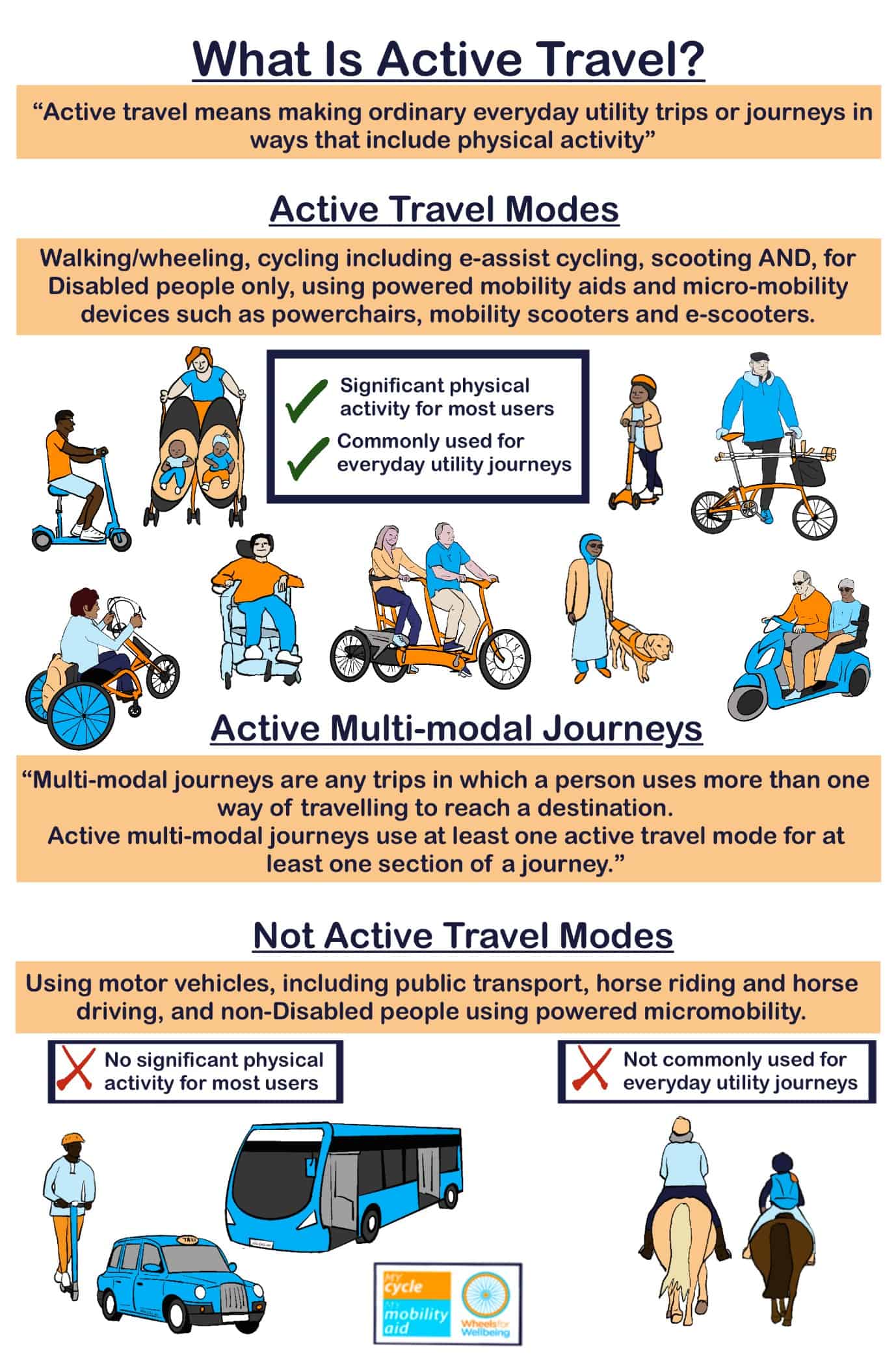

4.1.1 Active Travel

Equitable active travel matters because it can help to reduce the health and mobility gaps experienced by Disabled people.[69],[70] Active travel means making ordinary journeys, also called “utility trips”, in ways that include physical activity. Utility trips are trips made for any reason other than simply making the journey – going for a walk/wheel is not a utility trip: walking/wheeling to meet a friend in a specific place is. The most common active travel modes are walking/wheeling and cycling. We include all above-walking-speed modes that are comparable in size and movement to cycles, such as using mobility scooters, e-scooters and wheelchair power attachments as part of active travel, and we call these amplified mobility.

Active travel journeys may have any purpose – commuting, caring responsibilities such as school runs, shopping, medical appointments, social activities and more. Disabled people may use a range of mobility aids, powered and unpowered, to complete active journeys, including manual and powered wheelchairs, mobility scooters, rollators, crutches, canes, assistance animals and cycles.

4.1.2 Sustainable Travel

Sustainable travel is anything that reduces carbon output and other emissions that contribute to climate breakdown and air pollution. Public transport has lower emissions per person than private car or other motor vehicle use: even electric cars create pollution through particulates released from the tyres and when braking. Electric vehicles also have negative environmental impacts from their manufacture, disposal and the components they require. Simply switching from combustion engine to electric vehicles does not create the level of sustainability that we need.

More sustainable journeys involve active travel and/or public transport. Trips made using active travel and public transport together are called active multi-modal journeys.

However, many Disabled people cannot currently access public or sustainable transport and have to rely on a car or taxi for all or part of their journey.

Any changes in transport policy or provision must improve Disabled people’s mobility overall. This includes improving Blue Badge access and parking.

4.1.3 Multi-modal Journeys

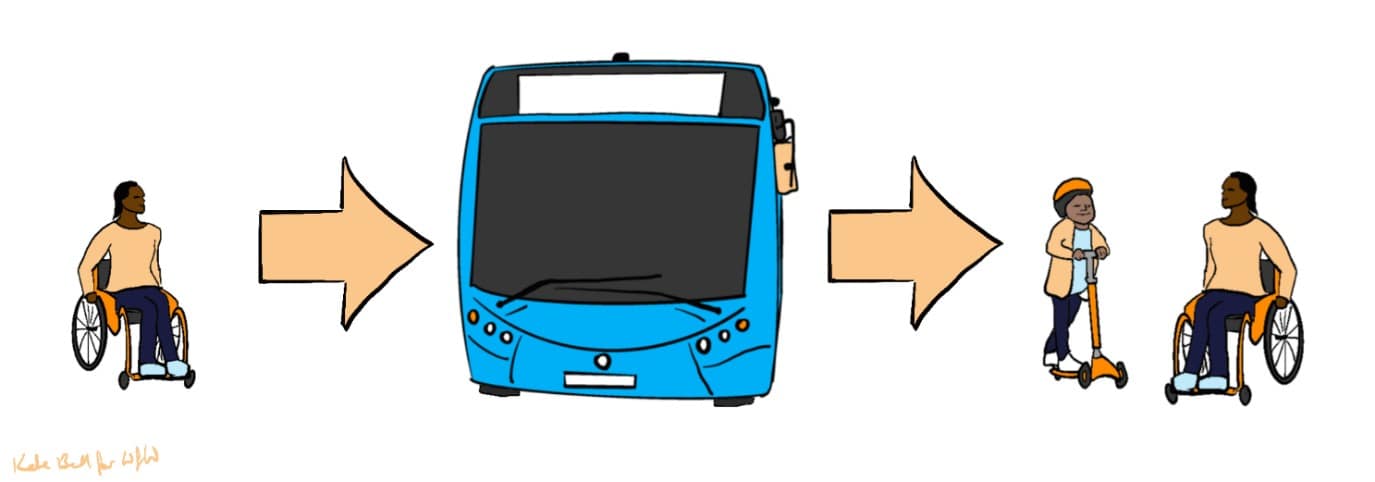

Multi-modal journeys are any trips in which a person uses more than one way of travelling to reach their destination. Active multi-modal journeys use at least one active travel mode for at least one section of a journey. This might include walking/wheeling or cycling to a bus, train or tram stop, or to a cycle hire or mobility hub, and then walking/wheeling or cycling the last section of the journey to the final destination.

4.1.4 Barriers to Active, Sustainable and Multi-modal Travel

The previous chapter highlighted some of the barriers to cycling faced by Disabled people, including infrastructure, parking and storage, cost, and harassment. Fully accessible cycling, active travel and multi-modal journeys require a wider spectrum of accessibility. This includes access to public transport for multi-modal journeys and the need for inclusive cycle centres and accessible cycle and micromobility hire/share schemes for sustainable journeys.

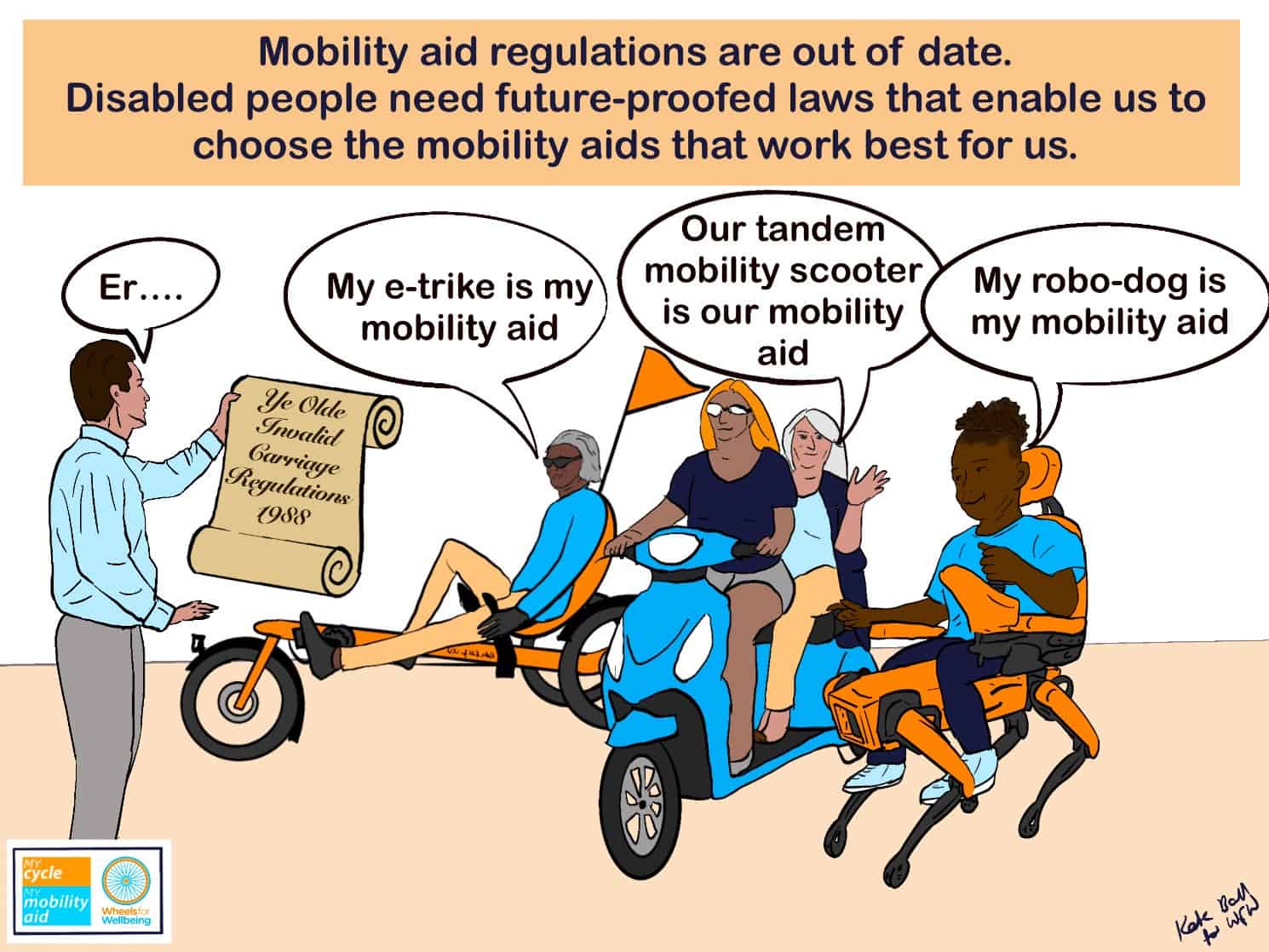

We believe that real progress towards making transport inclusively accessible can only happen with changes in legislation that allow Disabled people to use a much wider range of mobility aids in public spaces than are currently permitted by the “invalid carriage” regulations, including on public transport.