Download this position statement as a Word document

Download this position statement as a pdf

Waterside routes are being selected and upgraded to form part of active travel networks (see Canal and River Trust, Sustrans).

Benefits identified for waterside routes include access to nature and green/blue spaces for users, routes often being motor vehicle free, usually largely level, and often being administratively easier to upgrade or designate for active travel than road-adjacent routes, especially if carriageway reallocation would be needed. These factors (and others) mean sometimes waterside routes are being prioritised over creating LTN 1/20 and Inclusive Mobility compliant walking/wheeling and cycling infrastructure on nearby road routes.

Disadvantages of waterside routes often include lack of connectivity to destinations, lack of social safety (including lack of natural surveillance, isolation, lack of escape/turn options, lack of lighting etc) and physical hazards, including risks specifically associated with being near to water. If these disbenefits are not mitigated, waterside routes can exclude or disproportionately put people with protected characteristics at risk.

This sheet outlines evidence of risk and considerations required to mitigate the physical hazard of drowning for people using active travel routes adjacent to water.

A. Summary

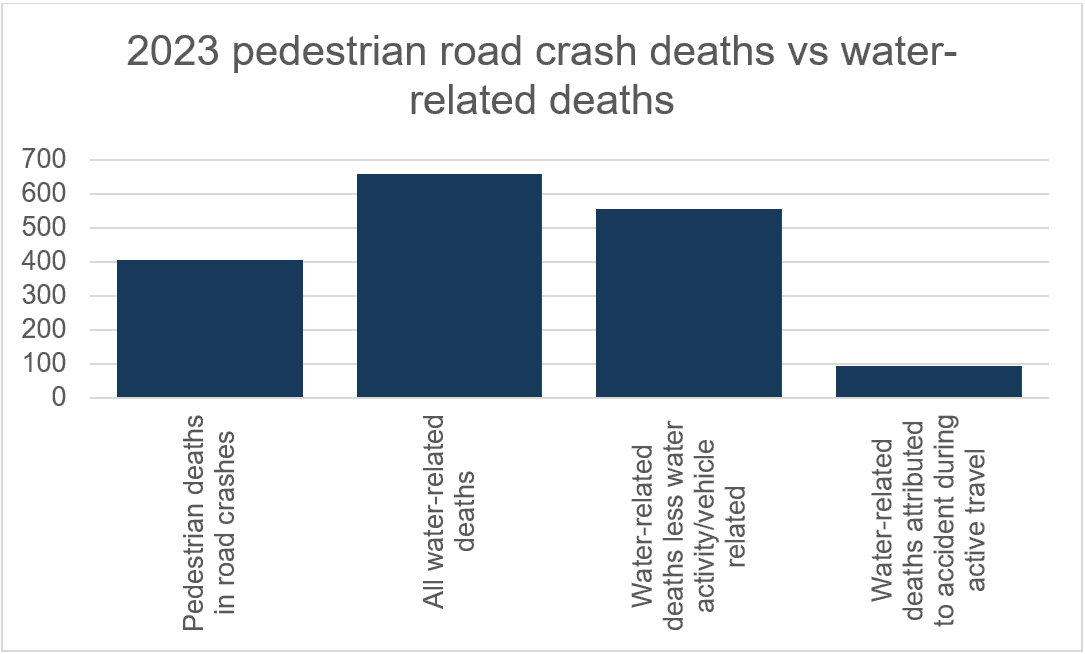

- In 2023 in the UK, the number of people drowning when using waterside routes was comparable to the numbers of pedestrians killed in collisions with motor vehicles (405 pedestrians killed in collisions, up to 555 people died after falling into water while not taking part in water-related activities, at least 93 of whom were walking/wheeling/jogging/cycling on a waterside route).

- The limited evidence presently available shows risk of drowning is likely to be much higher for people with protected characteristics, such as those from minoritised ethnic backgrounds, children and Disabled people.

- There are therefore significant equalities implications for understanding and mitigating risk from water hazards near to active travel routes.

- We have been unable to find any engagement from active travel planners, funders, designers and decision-makers with the risk of drowning that people walking/wheeling and cycling along water adjacent routes face. There do not appear to be any formal methods that active travel professionals can use to assess and mitigate risk to route users from route-adjacent water hazards. Current guidance on risk assessment for inland water from water and safety organisations has limited relevance to active travel route risk assessment.

- Increased promotion of waterside routes for active travel is likely to increase numbers of people drowning per year, unless infrastructure risk factors are recognised and mitigated. People at higher risk are likely to be prevented from making active journeys if route networks include sections with adjacent water hazards, unless sufficient safety mitigations or alternative safe, accessible and comparably direct route options are provided.

- Sections B and C of this discussion sheet outline factors which need to be assessed in order to mitigate risk of drowning for users of active travel routes adjacent to water. These factors are broadly in two categories:

- Infrastructure features which affect risk of water-related fatalities;

- Relative risk of water-related fatalities for people with different protected characteristics, and how these risks are affected by different route infrastructure features.

We urgently need the risk from water near to active travel routes to be recognised, assessed and appropriately mitigated.

B. Factors likely to affect risk of drowning on active travel routes

There are a huge range of factors which are likely to affect safety of individuals using active travel routes with adjacent water hazards. A few are suggested here:

- Proximity of route to the water’s edge – does the path run directly along the waterside or is there a beach, verge, hedge etc in between?

- Physical protection from the water – is there a railing, wall or fence?

- Water edge features – is there a vertical drop, or gentle shelving with/without planting to break falls? How deep is the water where someone could fall in?

- Alignment and gradient of route relative to water’s edge – does the route run parallel to the water, or are there sections where the path runs downhill towards the water? Is there crossfall tilting the path towards the water’s edge?

- Surface quality including on-surface and surface-adjacent hazards – is the surface sealed and smooth, or are there ruts, bumps and other imperfections which may cause swerves or crashes, including uneven edges or non-flush kerbs between any path and verge/protective strip?

- Weather and surface conditions – is the weather icy, wet, foggy or windy?

- Lighting conditions – is the route well lit at all times of day and night? Are there areas which are suddenly much darker than surrounding lengths such as tunnels which impede visibility even during daylight?

- Busyness of route – are route users likely to need to give way to others? How likely is it that people will be intimidated or hit by faster or more assertive route users? Is there space for a tricycle and a buggy (or double buggy) to pass?

- Relevant impairments, skill and experience of route user – safety of an individual is likely to be affected by how well they and people with them can perceive the route, others using the route and the likely movement of others, their agility and balance, and their control over any device they are using.

- Devices used – A person strapped into a seat or with their feet restrained is likely to be at much higher risk of drowning than a person who is not restrained. People who are commonly strapped in or restrained when using active travel devices include people using wheelchairs, handcycles and other non-standard cycle types, and children strapped into pushchairs, cycle seats and child cycle trailers.

A. Known risk factors for drowning relevant to active travel

There is limited evidence regarding individual risk factors relating to drowning.

There is also very limited evidence relevant to drowning while using water-adjacent active travel routes.

We have been unable to find any evidence about infrastructure-related factors associated with risk of drowning while using water-adjacent active travel routes.

Given the ongoing and increasing promotion of waterside routes for active travel, research is urgently needed to assess risks which specifically or overwhelmingly relate to walking/wheeling, cycling and other mobility aids.

Evidence on specific risk factors:

- Autistic people: CDC references a study showing 40x increased risk of drowning for autistic people, attributed mainly to autistic people walking near open water.

- Epileptic people: Drowning is identified as “the most common cause of death from unintentional injury for people with epilepsy” by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2019 policy statement).

- Blind and visually impaired people: RNIB states up to 15% of falls from rail platforms happen to Blind and VI people. This compares to around 3% of the population being Blind or visually impaired. It seems likely that unprotected drops into water near paths may be a comparable hazard to rail platform edges.

- Children from minoritised ethnic groups and socioeconomically deprived areas are drowning at much higher rates than average (2019-2021 data). 41 children drowned in 2023, with almost half drowning at inland water.

- Over 80% of people who drown in the UK are male.

- Reduced capacity related to alcohol and/or drugs – 14% of accidental drowning reports in 2023 noted presence of alcohol. This seems comparable to pedestrian impairment by drug or alcohol being given as a contributory cause in 9% of pedestrian road traffic deaths or serious injuries in 2019-2023 data.

B. Deaths from drowning vs pedestrians killed in vehicle collisions

In 2023, there were 659 water-related fatalities (drownings) in the UK, of which around 2/3 (around 440) were either accidental or had no attributed cause recorded, with the remainder being designated as suspected suicide or crime-related.

In comparison, in 2023, there were 405 deaths of pedestrians killed in collisions with vehicles on public highways. These people’s deaths are not separated by whether they are considered accidental, probable suicide or crime-related. There were 10 deaths associated with e-cycle/motorcycle and e-scooter fires in 2023.

Of the drownings deemed accidental, at least 39% of people who died (93 people) were walking, jogging, hiking or cycling near to water prior to their death, with up to 47% of water-related accidental deaths related to active travel[i].

Water-related deaths are not reported in the same way as road collision deaths.

The way water-related deaths are reported probably makes the number of people falling from paths and drowning each year look much smaller than it really is:For road collision deaths, any pedestrian who dies after being hit by a vehicle on a highway is counted, whatever else they may have been doing or thinking at the time of their death.

But for water-related deaths, people whose deaths are designated as suspected suicide or no attributed cause are effectively excluded from consideration by the way the annual reports only sub-analyse deaths that are judged to have been accidental.

This means that the numbers of people who died after falling into water when walking/wheeling or cycling along a path were probably much higher than the 93-112 reported (for 2023): It is likely that many of the people whose deaths were assigned as “no attributed cause” or “suspected suicide” should be included in statistics as people who were walking/wheeling or cycling along a waterside route prior to their death.

- Risk to people walking/wheeling and cycling from drivers of motor vehicles is well recognised. The need for mitigation of this risk is acknowledged in national government guidance, e.g. LTN 1/20, and ongoing measures intended to improve active travel safety.

- Risk to people walking/wheeling, cycling and using mobility devices in proximity to bodies of water is not well recognised. As such there is very limited recognition of the need to mitigate these risks for active travel routes.

Designating water-adjacent routes as part of active travel networks and encouraging their use through physical improvements and publicity is intended to increase the number of people walking/wheeling and cycling on these routes.

Unless there are simultaneous mitigations of the water hazard risk through safe route design, additional safety features and alternative provision, the number of people dying by drowning each year when using water-adjacent routes is likely to increase.

People with protected characteristics, including Disabled people, are likely to be disproportionately at risk of drowning when using water-adjacent routes.

[i] WAID 2023 annual reports and data: 5 “unknown activity”, 14 “waterside activity”- if these people are included, up to 47% of water-related deaths designated as accidental are related to active travel (112 people).