Celebrating 10 years of enhancing disabled people’s lives through cycling

This year, Wheels for Wellbeing is celebrating its 10th birthday. Earlier this month, the Beyond the Bicycle Conference brought together campaigners, local authorities, disabled people’s organisations, transport and health professionals to discuss the impact of the charity’s campaigning work and the future of inclusive cycling.

Click to download the conference slides.

On the 7th November London’s City Hall welcomed over 80 attendees for Wheels for Wellbeing’s Beyond the Bicycle Conference. The day was opened by the morning Chair Kamran Mallick, Chief Executive Officer for Disability Rights UK, with a keen observation that when he was a child, the NHS used to provide handcycles to their patients, something which, unfortunately, does not happen anymore today. “Sport is not an end goal in itself for people with disabilities”, says Mallick, thus arguing for the need for a more informed and broader understanding of disabled people’s mobility needs. Providing handcycles via NHS is just one such sensible approach. More generally, he highlighted the need to promote inclusive cycling; to recognise cycles as mobility aids and to make cycling infrastructure inclusive, all goals which Wheels for Wellbeing has espoused in the 10 years since its inception.

Isabelle Clement, Director of Wheels for Wellbeing, then took the stage to offer a glimpse into the journey of her organisation, nicely captured by the title of her presentation: ‘From “Cycling transforming disabled people” to “disabled people transforming cycling”’. The everyday lived experience of disabled people in Lambeth was the driving force for the creation of Wheels for Wellbeing, says Clement. One of the main struggles the charity faced, and continues to face, was to debunk the myth of cyclists as “very special and especially strong breed”. The common assumptions implied by inaccessible infrastructure are that all cyclists can levitate, walk their cycles, have 2 legs and 2 hands, ride on 2 wheels, lift their cycles and so on. “But this image of the cyclist does not fit with our reality”, argues Clement. “For everyone to cycle, we need a reconsideration of cycle infrastructure planning, cycle facilities design and to recognise that cyclists come in all shapes and sizes”.

Cycling as a mobility aid is not given the same status as other aids for disabled people, admits the next speaker, Rupert Furness, Head of Active and Accessible Transport, Department for Transport. The authority he represents aims nevertheless to tackle this issue through the Accessibility Action Plan, which aims to address the gaps in transport provision for disabled people. The document, published for public consultation, sets some ambitious goals: ensuring consistency in accessing transport services, monitoring regulatory compliance; enabling greater spontaneous travel and building confidence and empowerment.

The role of cycles for transport and as mobility aids for disabled people were also explored at local level by the next speaker, Lilli Matson, Transport Strategy Director at Transport for All. According to the Mayor’s Transport Strategy for London, which also aims to increase the trips walked, cycled or made by public transport to 80% by 2041, the Healthy Streets approach will benefit all cyclists. Matson told the audience that 15% of disabled people in London sometimes use a cycle to get around and 78% can cycle. London’s inclusive approach to cycling will require a change in both language and imagery, and the design standards for streets and parking facilities to accommodate ‘non-standard’ cycles.

Cycling transforming disabled people

The keynote speakers were followed by the next section of the conference, ‘Cycling transforming disabled people’, kicked off by Justin Varney, National Lead for Adult Health & Wellbeing (Healthy People), Public Health England. His presentation on how to use inclusive physical activity to reduce health inequalities opened with some worrying statistics: 37% of people with disabilities in the UK are not doing enough physical activity and those with mobility impairments make 363 fewer tips a year than the rest of the population. As part of the effort to create an active society, Public Health England has issued two strategies: Everybody Active, Every Day (2014) and Sporting Future (2015). While their ambition is noteworthy, with a five-year plan to spend £250 million to combat inactivity, there are still important challenges ahead, admits Varney: “There is still limited understanding of how to adjust Chief Medical Officers’ guidelines on physical activity for people with disabilities and impairments”.

The panel discussion that followed explored the benefits of cycling for disabled people and brought together the life stories of four disabled cyclists. Kay Inkle, Lecturer in Sociology at University of Liverpool, has done research on the negative perceptions and attitudes towards disabled cyclists and their role as barriers to cycling. “There is a disbelief that people with disability can cycle. I often heard people saying: ‘You have to walk here, you cannot cycle.’” The issue of perception was also highlighted by Leanne Wightman, Project Manager, Get Yourself Active, Disability Rights UK, but this time in relation to health practitioners. She presented the story of a disabled single mother who was refused the payment of an adaptation to her cycle, instead receiving one year worth of payment of a personal assistant. Dr Andrew Boyd, GP at Clapham Park Group Practice, confessed taking independence for granted until he had an accident that disabled him. Now he is an even greater advocate of ‘social prescribing’ for physical activity, which is effectively prescribing activities instead of medications. “We need to think about physical inactivity in the same way we think now about smoking”. Ed Clark from West Sussex County Council spoke about the inclusive cycling scheme that he runs in his local area and explains how they offer cycling opportunities both on and off-road. The council is able to offer access to the expensive and specialist cycles that many families could not afford to buy themselves. This introduces the importance of cycling hubs as one of the key components of inclusive cycling.

The conference then broke for lunch and, of course, birthday cake! The cake was cut by Wheels for Wellbeing Director Isabelle Clement and Wheels for Wellbeing Founder Janet Paske. The charity’s Beyond the Bicycle Anthem was also played (a remake of Queen’s Bicycle Race demonstrating some of the barriers faced by disabled cyclists, and bringing together some of the key campaigning asks in a very catchy and memorable way!).

After lunch the afternoon chair, Faryal Velmi, Director of Transport for All, opened the second half of the event: Disabled people transforming cycling.

Disabled People Transforming Cycling

Will Norman, Walking & Cycling Commissioner for London, delivered the afternoon keynote address of the conference. Echoing Lilli Matson’s presentation about the Mayor’s Transport Strategy for London, Norman reinforced that with the new ‘Healthy Streets’ approach, people will be at the heart of transportation. In a quest to ‘normalise’ cycling, Norman argues that we need to change “the way we talk, think, but also represent cycling”. For this, the role of infrastructure is essential, and he noted that the new Cycle Superhighways are no longer dominated by men in lycra: “Good cycling infrastructure is also good for disabled people”. Having worked closely with Wheels for Wellbeing over several months, Norman announced a ‘blue-badge’ type pilot scheme which will seek to recognise cycles as mobility aids and enable them to be used by disabled people in the same way and same places as mobility scooters and other mobility aids. He also mentioned that the current plans for the pedestrianisation of Oxford Street would not exclude disabled cyclists from using their cycles as mobility aids.

Mags Lewis, Spokesperson for the Green Party, tells her own experience of disabled cyclist, one which involves not cycling where it seems foreboding. She chooses instead the pavement, where, again she feels the environment is confrontational: ‘Too often as a disabled cyclist you feel you have to justify yourself’. Her solution to solve ‘most of the safety problems’ is simple and radical: 20mph zones in all towns. Dr Jamie Wood, Lecturer at the University of York and member of Empowered People, shared his experience of using his electric bike as his primary mobility aids. Isabelle Clement also joined this discussion and emphasised the importance of official recognition of the status of cycles as mobility aids. Without this, the actual or feared battles which individuals have to face are enough to create a huge barrier to people cycling as much as they could and wish to.

The next session was a double act of Neil Andrews, Campaigns and Policy Officer, Wheels for Wellbeing and Ian Plowright, Head of Transport, Croydon Council. Andrews began the session by launching the charity’s Guide to Inclusive Cycling. Based on a thorough consultation with disabled cyclists, engineers and academics, the guide covers three essential aspects to be considered when designing for inclusive cycling: building inclusive infrastructure, designing inclusive facilities and recognising disabled people as cyclists. Plowright shared how Croydon has begun to consider how to make their cycling offer more inclusive, and how they plan to use the guide to take this even further.

The final session considered the future of the relationship between cycling and disability. Rachel Aldred, Reader in Transport at University of Westminster, provided some interesting insights into the academic research on cycling and disability. According to the 2011 Census, 5.1% of cyclists in the UK have disability, versus 6.8% of all commuters Aldred also presented huge variation between local authorities on the participation of disabled people in cycling from 0.2% to 25.9%: “The main thing that determines cycle commuting rates for disabled people is how cycling-friendly the local environment is”. Her take-home message is that more research into both benefits and barriers to cycling is needed: “Very often groups under-represented in UK cycling could benefit most from it”.

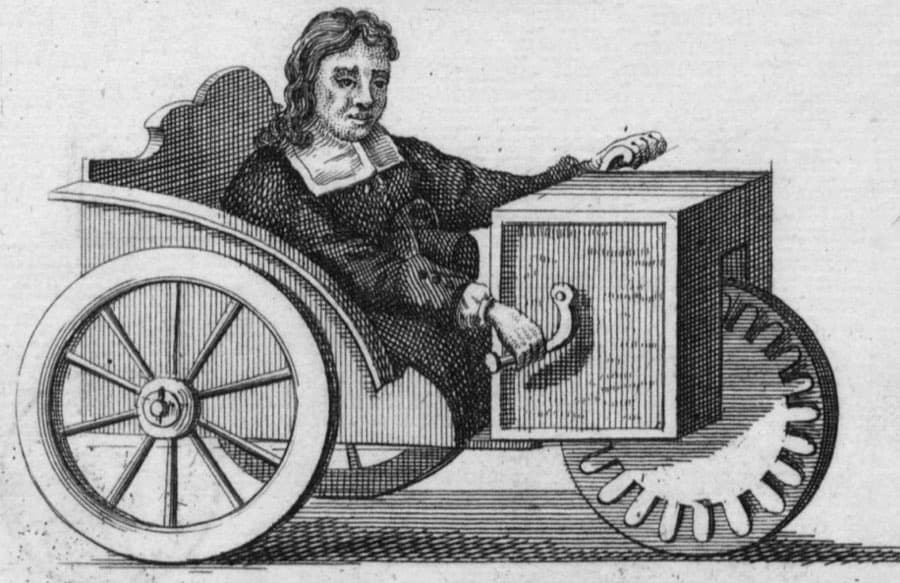

Kevin Hickman, trustee for Wheels for Wellbeing, who has long investigated the imagery of cycling in policy and design, argued that we need a change in the language used to describe cycling. To this aim, he presented the image of the first known disabled cyclist, Stephan Farffler, the 17th century inventor of this handcycle. Yet, none of the mainstream cycling historians acknowledges Farffler as ‘the first cyclist’, even though his invention precedes the now famous ‘draisine’, built only in 1817.

Cycling and disability

Finally, Ruth-Anna Macqueen, Co-Founder of the Beyond the Bicycle Coalition, presented this coalition between family cyclists such as herself, disabled cyclists as represented by Wheels for Wellbeing and Cargo Cyclists. They all face similar barriers (like not being able to dismount their cycles for barriers or steps or not being able to park their cycles) and are coming together to ask that infrastructure, facilities and imagery shows consideration of different types of cycles and moves “Beyond the Bicycle”. When this is achieved cycling will become truly inclusive and open to all.

[envira-gallery id=”2150″]